From Mission to Marketing: How Reformed Primary Schools Communicate their Value Proposition

Hivatkozás:

Duráczky Bálint & Nyüsti Szilvia & Mikó Fruzsina (2025). From Mission to Marketing: How Reformed Primary Schools Communicate their Value Proposition. Jel-Kép: Kommunikáció, Közvélemény, Média, (2.) 47-66. 10.20520/JEL-KEP.2025.2.47

Abstract

Since Hungary’s political transition, the number of faith-based educational institutions in Hungary, including those operated by the Reformed Church in Hungary, has expanded in several waves. The most recent surge, beginning in the 2010s (Papp 2022, Varga 2024), has led to the establishment of 181 reformed primary schools across the country (data source: Educational Authority’s Public Education Information System 2024). This rapid expansion has positioned the reformed school network as a potential competitor to the state education system. The most readily accessible and institution-controlled platform available for parents is the schools’ websites, where families can explore each institution’s self-defined value proposition and educational philosophy. This study examines the communication strategies of reformed primary schools in Hungary, focusing on how they present themselves through their websites. Using text analysis methods, we investigate how these schools emphasize their religious identity and differentiate their value proposition. We categorize schools based on their structural attributes and the composition of the student body, analyzing how these factors shape their communication and branding over time.

Keywords

Introduction

The Hungarian educational landscape has witnessed a notable resurgence and expansion of faith-based institutions since the political transition, altering the dynamics between state and religious schooling. Within this trend, the Reformed Church in Hungary has significantly increased its footprint, particularly in primary education, following surges that began in the 2010s. This growth establishes a robust network of Reformed primary schools, presenting them as accessible alternatives and potential competitors to the state system for attracting students. For parents navigating school choices, institutional websites serve as crucial initial contact points, offering insights into each school’s unique ethos and educational philosophy. Understanding how these schools leverage their online presence to articulate their identity is therefore essential. This study examines the website communication strategies of Hungarian Reformed primary schools, focusing specifically on how they convey their religious values and overall value proposition to prospective families, and how these messages may vary based on the school’s characteristics. While the analysis identifies patterns in the relationship between communication practices and institutional features—such as school size or student composition—it does so within a descriptive framework. Rather than offering causal explanations, the study aims to map and interpret the diversity of value communication as it relates to school selection dynamics. Due to its descriptive nature, the research does not operate with predefined hypotheses; instead, it seeks to provide an empirically grounded overview of existing practices and emerging patterns. The focus on Reformed institutions provides a homogeneous analytical context, where differences can be attributed primarily to structural, student-related, or communicative factors; the research may later be extended to institutions under other types of maintainers.

Church-Run Institutions in Hungary

As in many European education systems, church-run educational institutions have played a defining role in the history of education in Hungary (Kodácsy-Simon 2015). Following the Communist Party’s rise to power, the Parliament passed Act XXXIII of 1948, nationalizing schools, which placed 6,505 schools under state control. Almost without exception, these were church-run institutions, with 5,407 being primary and elementary schools. The number of Reformed elementary schools brought under state control was approximately 1,200 (Horváth 2016). Before the political transition in Hungary, the Németh government, particularly the subsequent Antall government, took decisive steps to re-establish the legitimacy of church-run institutions. Thus, from the year of the regime change onwards, educational activities were reorganized in some of the previously closed institutions (Drahos 1992).

However, the size of the school system has never returned to its pre-communist takeover levels. A decade after the regime change, in 2001, only 144 church-run primary schools were operating at 150 locations. The next decade did not bring significant expansion either: by 2010, 197 primary schools were operating at 233 locations. After 2010, the expansion of the church-run education system accelerated, with a focus on primary schools. The number of service locations doubled within four years, reaching 467 by the 2014/2015 academic year (Ministry of Human Capacities 2020). The pace of expansion slowed in the subsequent years but gained momentum again in the early 2020s, marking the third wave of re-establishing the church’s role in the education system. By 2024, 421 church-run primary schools operated at 594 locations, accounting for 16.9% of the entire primary school segment.

The expansion described above also defined the role of Hungary’s second-largest church, the Reformed Church in Hungary. In 2024, Reformed Church-run primary schools operated at 181 locations, accounting for 5.1% of the entire segment. The distribution of Reformed schools is uneven across the country, with the social presence of the Reformed denomination typically stronger in eastern and northeastern Hungary. As a result, many of these institutions are in the eastern part of the country. In this region, the Reformed school system, due to its size, has become a readily accessible alternative and ultimately a competitor to the state-run education system.

Competition Between State and Church Institutions

The phenomenon of parallel structures and their consequences can be analyzed from various perspectives. Numerous examples of such analyses can be found in the Hungarian academic literature. Without aiming for completeness, some focal points of these studies include educational added value (Bacskai – Ceglédi 2023), state-church relations (Neumann 2025), access and equity (Neumann – Berényi 2019), funding (Péteri – Szilágyi 2022), comparisons of teaching staff (Bacskai 2007), and the impact on the development of religiosity (Pusztai – Rosta 2023). However, this parallel can also be explored within the context of a supply-and-demand-driven competitive market, where institutions strive to maintain the desired intake numbers across successive cohorts. Nevertheless, this competitive context can only manifest within certain limits in the public education sector, as legal regulations restrict the geographic recruitment area and the number of students that an institution can admit. Despite these limitations, schools can still be viewed as competing actors. This is most clearly evidenced by the range of articles addressing educational selection and segregation, which point out that, in scientifically documented cases, a change in the school maintainer results in a shift in the student population’s social background (Papp – Neumann 2021, Neumann 2025).

In this competitive context, the ability to differentiate as an institution becomes crucial. As emphasized in marketing and strategic literature, one of the fundamental tools of market differentiation is the clear articulation and communication of a Unique Value Proposition (UVP), which forms the core of a business strategy (Payne – Frow 2014). For educational institutions, these value propositions often include the values (whether religious, pedagogical, communal, or other principles) with which the institution identifies and represents, addressing the needs and preferences of its target audience (cf. Porter 1985). When an institution effectively communicates these values, it can attract precisely those parents and students for whom these values are of primary importance in the school selection process. Thus, the values represented and conveyed by the institution become the central element of its value proposition, enabling the school to differentiate itself from other actors (Porter 1985) and successfully secure its enrollment numbers by attracting a “demand” that shares the same values.

However, when it comes to church-run institutions, particularly those operating in the education sector, articulating a coherent and distinctive value proposition becomes more complex. While religious marketing has been recognized as a distinct subfield within nonprofit and services marketing (Wrenn 2010, Juravle et al. 2016), the literature reveals that it lacks a well-developed empirical foundation and is often marked by conceptual ambiguity. Religious organizations, due to their symbolic mission and value-driven nature, often do not conform to the functional and strategic logic typically associated with marketing practices. As Abreu (2006) shows in his analysis of the Catholic Church’s brand image, the values communicated by religious institutions often appear inconsistent or diffuse and not aligned with a strategic brand position. This raises challenges for faith-based schools, where it remains an open question whether these institutions communicate primarily as educational service providers, responding to parental expectations and competitive pressures, or as extensions of a broader ecclesiastical mission.

Beyond general marketing strategies, there are also societal reasons why it is increasingly important for schools to project their institutional identity and embrace values. Two mutually reinforcing processes can be highlighted to support this claim. On the one hand, a completely secular perspective can be considered. Parental awareness is rapidly increasing. School selection requires increasingly extensive information gathering by parents who are becoming more discerning. Decades ago, a broad segment of society chose the local district school. However, today, with the possibility of more open school choice and increasing competition between institutions, parents actively seek and evaluate the unique value propositions offered by various schools. The institution’s pedagogical program, educational philosophy, specializations, community atmosphere, reputation, and, not least, the values and ethos it represents are included. The goal for parents is to find an institution that best aligns with their expectations, values, and their child’s perceived or actual needs (Berényi et al. 2005, Cucchiara – Horvat 2014, Jabbar – Lenhoff 2019).

On the other hand, a perspective related to religious change is also worth mentioning. While the educational role of churches has been rapidly expanding since 2010, census data indicate that religious affiliation as a social norm has been eroding even more swiftly. In Hungary, the first census to include a question about religious affiliation was conducted after the regime change in 2001. The previous data point dates to 1949. While 97.88% of the population identified as belonging to a religious denomination in 1949, this figure had dropped to 73.68% by 2001, marking a decline of 24 percentage points. Although this 24-percentage-point decline may seem significant, the explicitly anti-religious decades of the socialist regime make it somewhat unsurprising. However, the decline from 2001 to 2022 accelerated dramatically, with the percentage of people identifying with a religious denomination plummeting from 73.68% to 41.97%. It is worth noting that a 32-percentage-point drop has occurred following a 24-percentage-point decline over 50 years, all in just 20 years. Moreover, younger generations, including today’s parents and children, are even less likely to identify with a religious denomination. Consequently, year by year, there are fewer students in church-run schools with a religious upbringing or strong church affiliation. Therefore, the mere fact of church governance is no longer sufficient as a value proposition. To maintain and increase enrollment, church-run institutions must articulate values or identities that extend beyond church affiliation but remain connected to it, effectively targeting the increasingly discerning parents seeking schools for their children.

Value Dimensions of Church-Run Institutions

Only a few studies have focused on the values and identity of church-run schools in Hungary. One such study, examining the identity of Reformed secondary schools, identified various value dimensions—such as tradition preservation, reinterpretation, and a focus on effective education—where institutional identity was often shaped by religious activities (Kopp 2005). Another study highlights the role of teachers, who, on average, tend to be more religious and place greater emphasis on general Christian values such as responsibility, respect, and honesty. In addition to education, they also prioritize character development and spiritual guidance (Bacskai 2008, 2009). Another study comparing state and church-run schools confirmed that while teachers in church-run schools share many core values with their colleagues in state schools, they place significantly greater emphasis on religious faith as an educational value (Major et al. 2022). Thus, the value system and identity of church-run schools, although varying in emphasis across institutions, can indeed serve as a distinguishing feature and a unique value proposition for parents in a secularizing social environment.

Parents have various sources of information when selecting a school. Open houses, public demonstration classes, social media, and conversations with preschool teachers or other parents can all influence their decisions. In these cases, the messages received by parents are shaped not only by the values and ethos communicated by the school’s leadership but also by the impressions left by a teacher’s presentation or the experiences shared by other parents. In contrast, the school’s website and the written documents available on it can convey the institution’s self-image and value proposition more directly. Theoretically, the information provided on the website is undistorted, as it is shaped solely by the intentions of the school’s leadership. However, an empirical study conducted in Spain highlights that institutional websites often exhibit general shortcomings, such as unappealing design, lack of information, outdated content, and limited information about teaching conditions and pedagogical methods (Álvarez Herrero – Roig-Vila 2019). Despite these challenges, several studies rely on the content of school websites (Dimopoulos – Tsami 2018, Tardío-Crespo – Álvarez-Álvarez 2018, Gilleece – Eivers 2018). Noteworthy among these is a study conducted in Ireland, which examined the online identity of church-run schools (Wilkinson 2020). The 2018 study, which analyzed the websites of 74% of schools, sought to understand how these institutions use their online platforms to present their identity and ethos. The study found that a significant portion of schools (35%) did not clearly indicate their religious affiliation on the homepage; in some cases, this information was absent. The analysis of ethos statements revealed that many schools relied on a 2003 template document, suggesting a lack of effort in developing a distinct school ethos. The study also found that elements essential to institutional identity, such as episcopal support, parish connections, school congregations, and the specifics of religious education, often appeared inconsistently or were entirely missing from the websites. Uncertainties also emerged in the communication of values and inclusivity.

Given the country-specific educational, cultural, and institutional contexts, it is not self-evident that similar findings would emerge in the Hungarian setting. However, prior research supports the notion that content analysis of school websites is a viable and informative method for uncovering characteristic differences and institutional patterns in value communication. The empirical studies based on website analysis referenced above are methodologically relevant to the current study, which examines data collected from the websites of Reformed Church-run primary schools in Hungary, as will be presented in the following chapters.

Methodology

Target Group of the Analysis

The target group of this research consists of church-run primary educational institutions operating under the Reformed Church in Hungary, regardless of the level of the church organizational structure (e.g., church, diocese, parish) that serves as the maintainer. According to data from the Educational Authority’s Public Education Information System (KIR) for October 2024, this segment included 117 institutions providing primary education and their 181 service locations under supervision.

As indicated by these figures, educational institutions in the public education system may have multiple service locations operating in different geographical areas, possibly even in different municipalities, compared to the leading institution. These service locations, while geographically separate, fall under the same institutional management, governance, and professional oversight. Despite the legal subordination, the practical integration of service locations can vary significantly, ranging from substantial differences in professional unity, management and governance practices, resource sharing, as well as organizational culture and communication. These discrepancies are partly due to the current institutional structure evolving, not through organic development, but rather through institutional transformations and maintenance changes driven by policy decisions. This structural diversity, which is evident in everyday operations, is not easily discernible from legal and administrative records. However, it becomes strikingly apparent in online communication practices, particularly in the context of institutional websites. During the examination of the websites of primary schools, it became evident that the online representation of the relationship between institutions and their service locations is highly heterogeneous. In some cases, service locations are presented as sub-pages within the primary institutional website, with a distinct structure and content. In other cases, only minimal information is available about these units, without a substantial independent online presence. There were also instances where the service location had its website, significantly different in structure and content from that of the leading institution, effectively functioning as an independent online platform. This diversity illustrates the varying degrees of institutional integration and the complexity of online communication practices.

Considering that parents primarily select schools for their children based on specific service locations rather than the overarching institution, the initial sample included all 181 service locations associated with Reformed Church-run primary schools. However, due to differing practices concerning the integration of institutional-level online communication, the scope of the analysis needed refinement. The final analysis concentrated on primary schools that had a standalone website or a distinct sub-page within the institutional website dedicated to specific service locations. Consequently, service locations that lacked their website or any content representing them on the primary institution’s website were excluded from the study as independent analytical units. After this refinement, we analyzed 135 websites or sections of websites that covered all currently accessible Reformed Church-run primary school websites.

It should be noted that the final set of 135 websites or sub-pages continues to reflect the complete institutional population of Reformed Church-run primary schools. The reduced number, compared to the initial 181 service locations, is due to the lack of independent online representation for some service units, which do not operate separate platforms distinguishable from the primary institution’s website. While the numerical distribution of the displayed value dimensions is projected across the complete set of 181 service locations, the subsequent qualitative interpretation of these dimensions is naturally limited to the narrower sample of institutions with actual, content-bearing online presence.

Methods of Analysis

The objective of the research is to explore how Reformed Church-run primary schools articulate their value orientations and pedagogical profiles through their online platforms. To achieve this, website analysis and content analysis methods were employed. Given the extensive and diverse content of the websites, as well as the various formats for information dissemination (e.g., videos, images, links to external resources, uploaded documents), a comprehensive text analysis of the entire websites was not feasible. Therefore, the scope of content analyzed was refined to focus on specific elements.

One segment of our methodological approach, specifically the content analysis pillar, focused on identifying intentionally articulated and well-defined content units within the websites that could serve as expressions of school ethos. The selection criterion was that a given subpage—regardless of its format or title—should meaningfully convey the institution’s self-representation, history, values, and educational philosophy. Based on this criterion, sections such as “Introduction”, “Our Mission”, “Our History”, “About Us”, “Principal’s Greeting”, and other similarly themed pages (e.g., “Our Story”, “Mission”, “Our Program”, “A Letter to the Reader”) were included. Significant variations were observed in the naming and content structure of these subpages. Some institutions conveyed their mission statements concisely and directly, while in other cases, value communication was embedded within historical overviews or personal, narrative-style greetings from the principal. These identified content-rich subpages formed the basis for content analysis, which was conducted using the NVivo qualitative data analysis software.

The other methodological pillar involved the targeted content analysis of the websites’ menu structures. Following a predefined set of criteria, we examined whether specific socially and educationally relevant values were represented as prominent, standalone menu items in the schools’ online communication. This analysis was based on a keyword structure that encompassed thematic areas typically emphasized in the mission and educational goals of public educational institutions. It focused on the following key categories: Religion, Community, Excellence and Achievements, Equity, Traditions and Cultural Heritage, Sustainability, Social Engagement, Education for the 21st Century, Internationalization, Exercise and Sports, and Infrastructure and Facilities. The objective of the structured menu analysis was to map the prominence and visibility of these themes on the schools’ websites, indicating the institutional importance and self-representative role of each value dimension.

To ensure accurate data capture, the narrative text elements were manually collected from the institutional websites, while their subsequent coding and analysis were conducted using NVivo. In contrast, both the collection and coding of the menu structures were carried out manually, due to their highly heterogeneous and often complex architecture and content. The coherence between the two analytical approaches – the examination of subpages containing narrative texts and the menu structure – was ensured through a standard keyword structure and interpretative framework. During the content analysis, the frequency of 220 keywords related to the 11 thematic dimensions was coded using NVivo. In contrast, the objective of the menu structure analysis was not to identify literal keyword occurrences but to assess thematic alignment: whether the names of the menu items reflected the specified values, educational objectives, or institutional priorities.

The information gathered from analyzing narrative texts and the menu structure was consolidated into a unified SPSS database. This was then subjected to multivariate analysis, which included background variables characteristic of the institutions and service locations. Thus, the methodology enabled a structured comparison of value preferences and institutional identities despite the diversity of formats and communication practices.

Since the analysis relies on comprehensive data collection, a full-population analysis was conducted; therefore, sampling error is not a relevant factor. Consequently, the application of hypothesis testing was not deemed necessary for reporting the results.

Institutional Background Variables

The analysis also examines how the values communicated through websites differ based on the structural characteristics of schools and the composition of their student bodies. To capture structural characteristics, institutions were grouped using cluster analysis based on the number of students, the content of tasks performed, and the proportion of primary school students within each institution. As a result, four segments were identified: 1.) Small, exclusively primary education institutions (37%); 2.) Medium-sized, exclusively primary education institutions (37%); 3.) Large, exclusively primary education institutions (14%); 4.) Multi-purpose institutions (12%).

The composition of the student body was also analyzed using cluster analysis. Factors considered included the proportion of disadvantaged or multiply disadvantaged students, the presence of students with special educational needs (SEN) or those struggling with integration, learning, or behavioral difficulties, and the proportion of students commuting from other municipalities. Based on these factors, four segments were identified: 1.) Regional centers with favorable backgrounds (28%); 2.) Institutions facing combined social and educational disadvantages (8%); 3.) Local institutions with favorable backgrounds (47%); 4.) Institutions with a high concentration of behavioral, learning, and developmental issues (17%).

Analytical Limitations

One important aspect of the analysis is that the presence, structure, and frequency of content updates on school websites largely depend on the availability of local digital infrastructure and the technological competencies of human resources. Consequently, the content presented on these websites may not fully reflect the educational ethos or actual functioning of the institution, as technical constraints may shape and limit the information provided. Despite these limitations, school websites play a crucial role in informing parents, especially when other direct sources of information are unavailable. Therefore, while technical and competency-related limitations affect data interpretation, they also provide valuable insights into the quality of schools’ digital communication practices. The public and easily accessible nature of school websites makes them particularly significant for parental decision-making, highlighting their role as primary sources of information when alternative means are not available.

Results

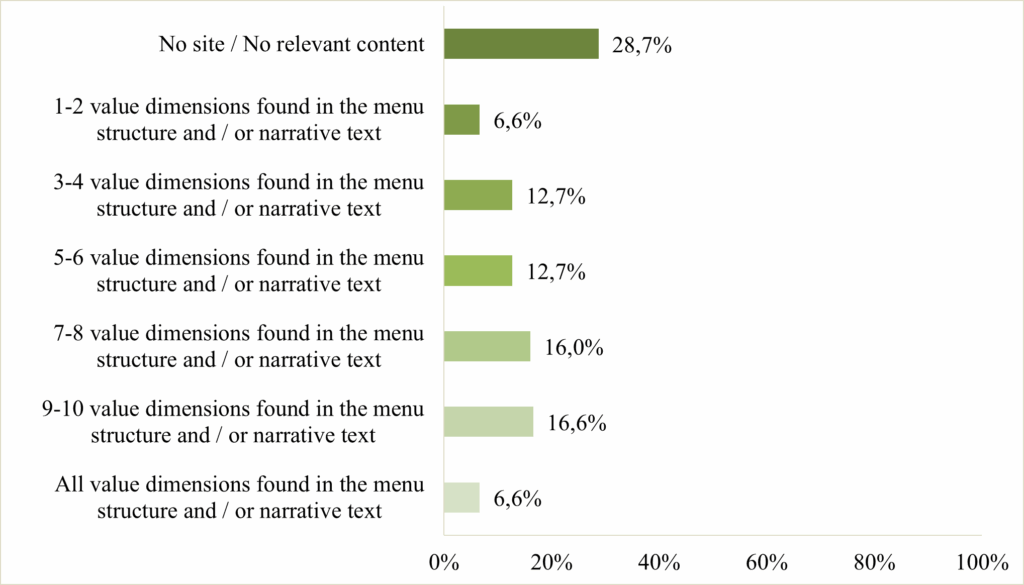

The Reformed Church-run primary school service locations communicate an average of 4.7 value dimensions through their websites. However, in 28.7% of cases, no value proposition is conveyed through either narrative content or the menu structure on the website. This can be partly explained by the complete absence or inaccessibility of the website and partly by the lack of articulation of the examined value dimensions. The two extremes in the sample are represented by institutions that communicate only 1–2 value dimensions (approximately 7%) and those that convey all 11 examined dimensions (also approximately 7%) (see Figure 1). Among school websites conveying no more than two of the analyzed value dimensions, the “Excellence and Achievements” dimension was most frequently emphasized, often in isolation, as the only explicitly communicated value.

Figure 1.

Distribution of institutions based on the number of value dimensions communicated on their websites (N=181; %)

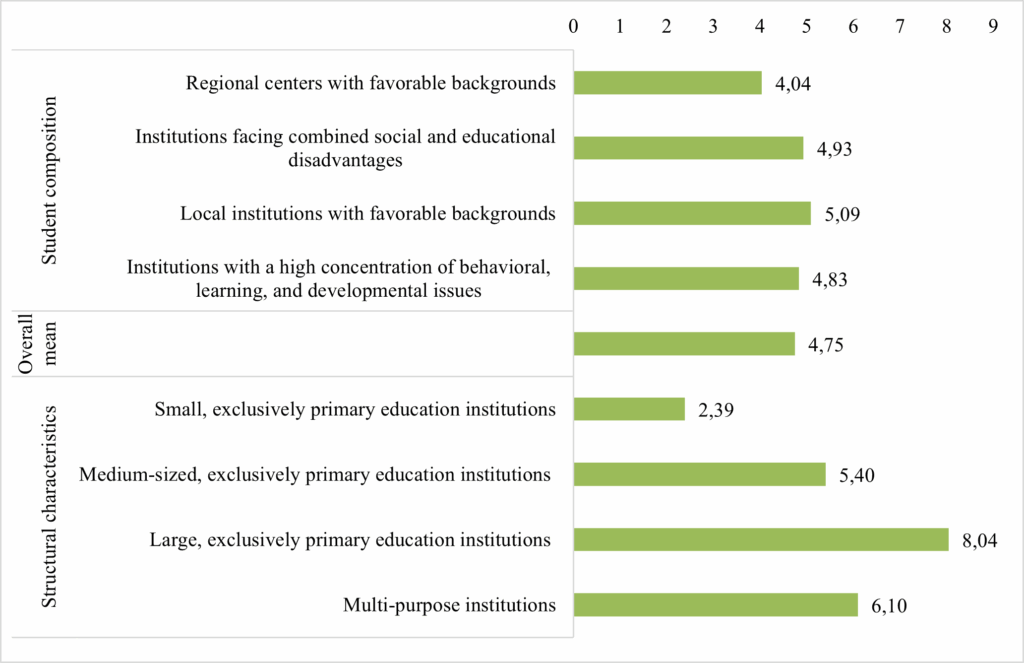

The number of communicated value dimensions appears to be less affected by the composition of the student body; regardless of the student body composition, institutions typically present an average of 4–5 value dimensions on their websites. In contrast, when institutions are categorized based on structural characteristics, significant differences arise, primarily linked to the institution’s size. The larger the institution, the more value dimensions are conveyed through the website (see Figure 2).

The subsequent analysis focuses exclusively on schools with active websites and pertinent subpages. The next chapter outlines how frequently the analyzed value dimensions appear in the narrative content of the relevant subpages and the menu structures of the analyzed websites.

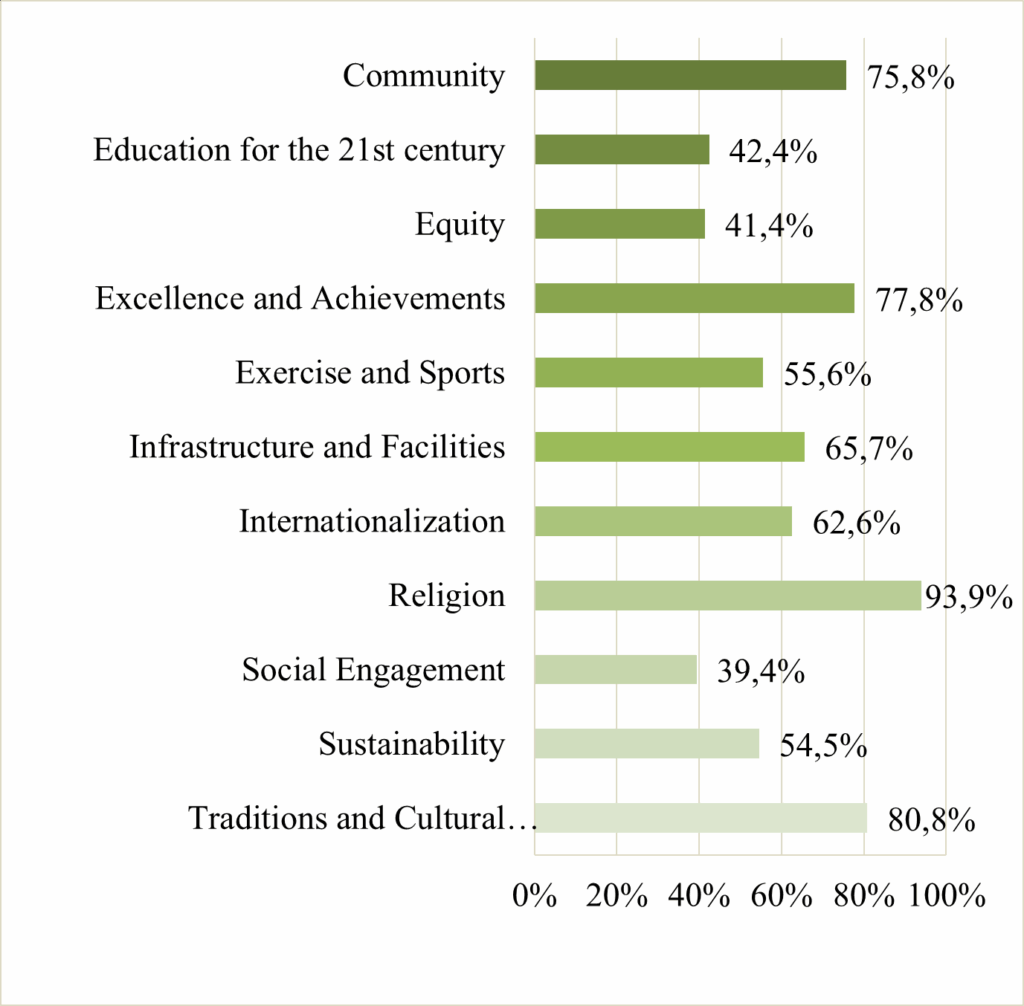

Relative frequency of value dimensions

As previously mentioned, during the content analysis, 11 value dimensions were facilitated by a set of 220 keywords. In analyzing narrative texts, a value dimension was considered present if at least one associated keyword (or some grammatical variation of the keyword) appeared in the text. The figure below illustrates the frequency of occurrence of value dimensions. Among the narrative texts, the “Religion” value dimension appears most frequently, being present in 93.9 percent of the analyzed texts. The second most common value dimension is “Traditions and Cultural Heritage,” which can be found in 80.8 percent of the texts. The “Excellence and Achievements” dimension is present in 77.8 percent of the texts. Thus, intellectual, moral, and cultural core values are prominently represented in most of the analyzed texts, and institutions also frequently emphasize their achievements and areas of pride. In contrast, the “Education for the 21st century,” “Equity,” and “Social Engagement” value dimensions appear in less than half of the texts. Topics such as decision-making, social inclusion, equity, justice, support for disadvantaged groups, and the challenges and opportunities of the digital world are therefore less emphasized in the narrative texts published on the websites (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Average number of value dimensions communicated on websites by institutional clusters (N=181; units)

Figure 3.

Relative frequency of value dimensions in narrative texts (N=99; %)

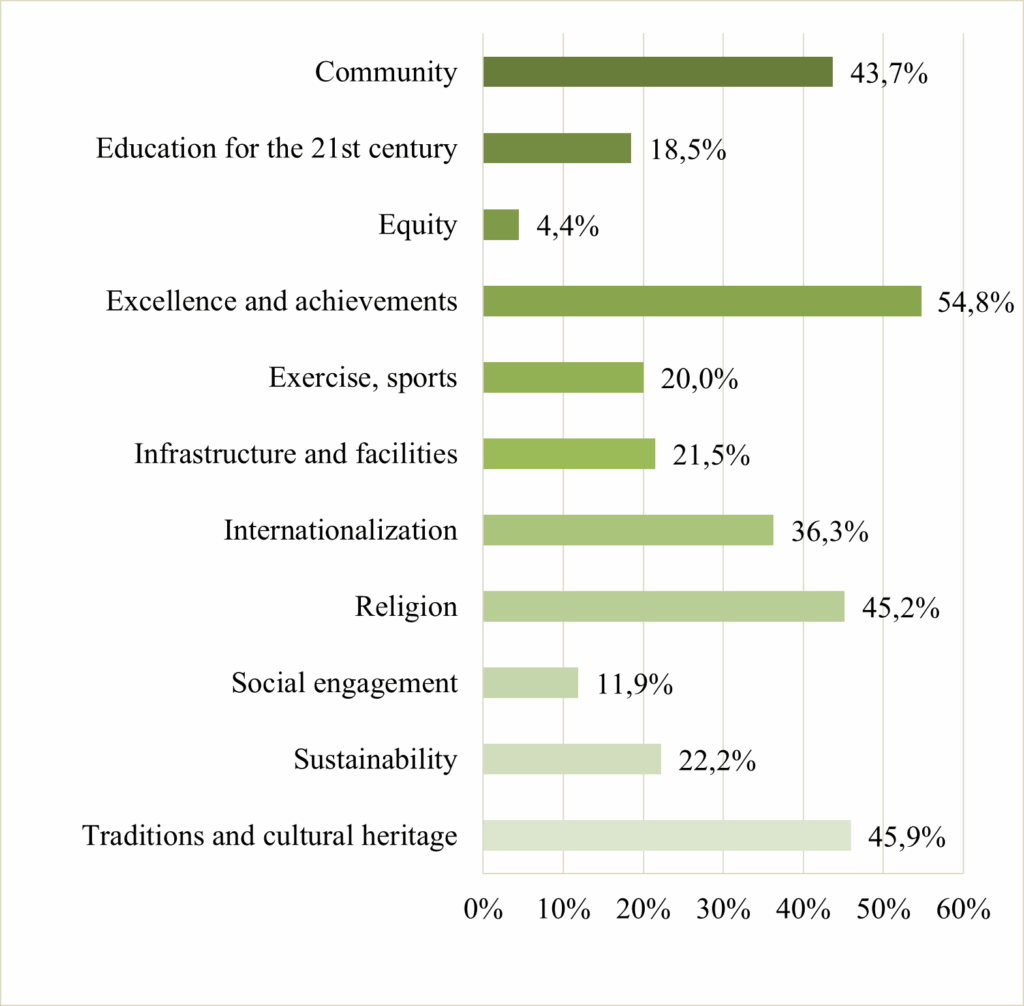

Figure 4 illustrates that the “Excellence and Achievements” value dimension is the most prominently featured in the menu structures of the analyzed websites, appearing in 54.8 percent of them. This is followed by the “Traditions and Cultural Heritage” value dimension, which is present in the menu structures of 45.9 percent of the websites. Menu items related to faith and religion appear on 45.2 percent of the websites. Thus, these three value dimensions are the most frequently represented in the menu structures, as in the narrative texts, albeit in a different order. The theme of excellence and achievements is more prominently featured in the menu structures than the religious themes. The least represented value dimensions in the menu structures are “Equity” (4.4%), “Social Engagement” (11.9%), and “Education for the 21st century” (18.5%). These also align with the value dimensions least emphasized in the narrative texts.

Figure 4.

Relative frequency of value dimensions in menu structures (N=135; %)

In the previous sections, we presented the results of the analysis of narrative texts and menu structures independently and in parallel. However, if certain value dimensions appear from both perspectives within the same institution, it can be inferred that these themes receive particular emphasis in the institution’s communication. The following chapter provides insight into this aspect.

Identification of Prominently Communicated Value Dimensions

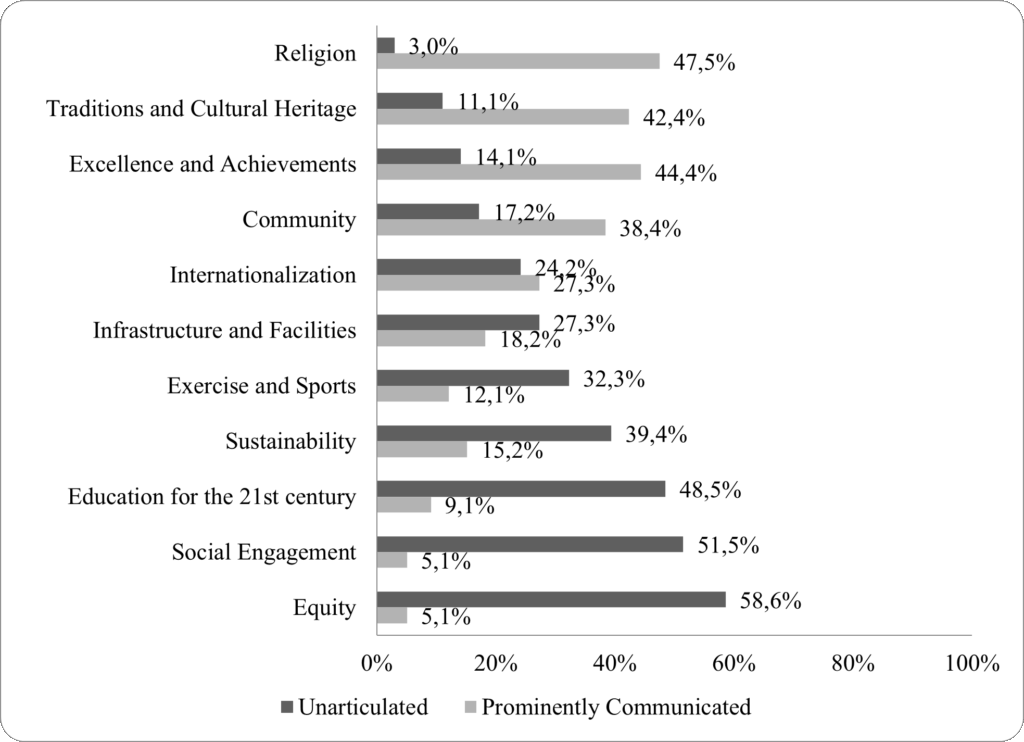

The analysis places particular emphasis on identifying value dimensions that are not only present in narrative texts—such as institutional introductions, mission statements, or principal’s greetings—but are also explicitly highlighted in the menu structure. This dual presence indicates a deliberate and emphasized institutional communication of a given value, as its inclusion at the menu level suggests that the dimension holds a prominent role in the external representation of the school. The joint consideration of narrative content and menu architecture is grounded in the assumption that both reflect institutional-level decisions about what is worth highlighting and how the school wishes to present itself to the public. While narrative texts allow for more nuanced or symbolic articulation of institutional values, menu items represent high-level, navigational signposts that organize and prioritize content for users. A value that appears simultaneously in the school’s self-descriptive texts and its structural layout signals not only intentionality but also consistency in its public-facing identity. In the analysis, these are referred to as prominently communicated value dimensions, as their presence is not merely implicit but can be observed across multiple layers of the schools’ digital self-representation. In contrast, value dimensions that do not appear in either analytical context are considered unarticulated values, meaning they are not publicly conveyed through the websites.

The results indicate that in the online self-representation of Reformed Church-run primary schools, specific value dimensions — particularly “Religion” (47.5%), “Excellence and Achievements” (44.4%), “Traditions and Cultural Heritage” (42.4%), and “Community” (38.4%) — frequently appear as prominently communicated values. Among these, the “Religion” dimension stands out, with only 3 out of 100 institutions not articulating it on their websites. Conversely, values that are considered significant in contemporary educational discourse, such as “Equity” (5.1%), “Social Engagement” (5.1%), and “Education for the 21st century” (9.1%), are markedly underrepresented in this combined analysis. These values are emphasized by only one in ten or twenty institutions and are absent from the online presence of approximately half of the schools (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Occurrence of prominently communicated and unarticulated value dimensions on websites (N=99; %)

In the previous sections, the results were presented independently of institutional background variables. The following chapter focuses on which value dimensions exhibit the broadest range of variations in communication across institutions or service delivery sites, and which ones show a more consistent frequency depending on background variables.

Patterns of Homogeneity Based on Student Composition and Institutional Structure

The analyzed service locations were categorized into four groups based on student composition and four groups based on institutional structure (see the “Institutional Background Variables” section). Cross-tabulations were used to examine the proportion of value dimensions mentioned in the narrative texts according to these background variables. For some value dimensions, significant differences emerged based on these background variables, while for others, the frequency of mentions remained relatively consistent across the groups. To identify which value dimensions were communicated consistently and which were more influenced by student composition and/or institutional structure, we examined the range between the lowest and highest relative frequencies for each value dimension in both background variables. The analysis below does not examine the precise frequency of each value dimension within the narrative texts of the respective clusters.

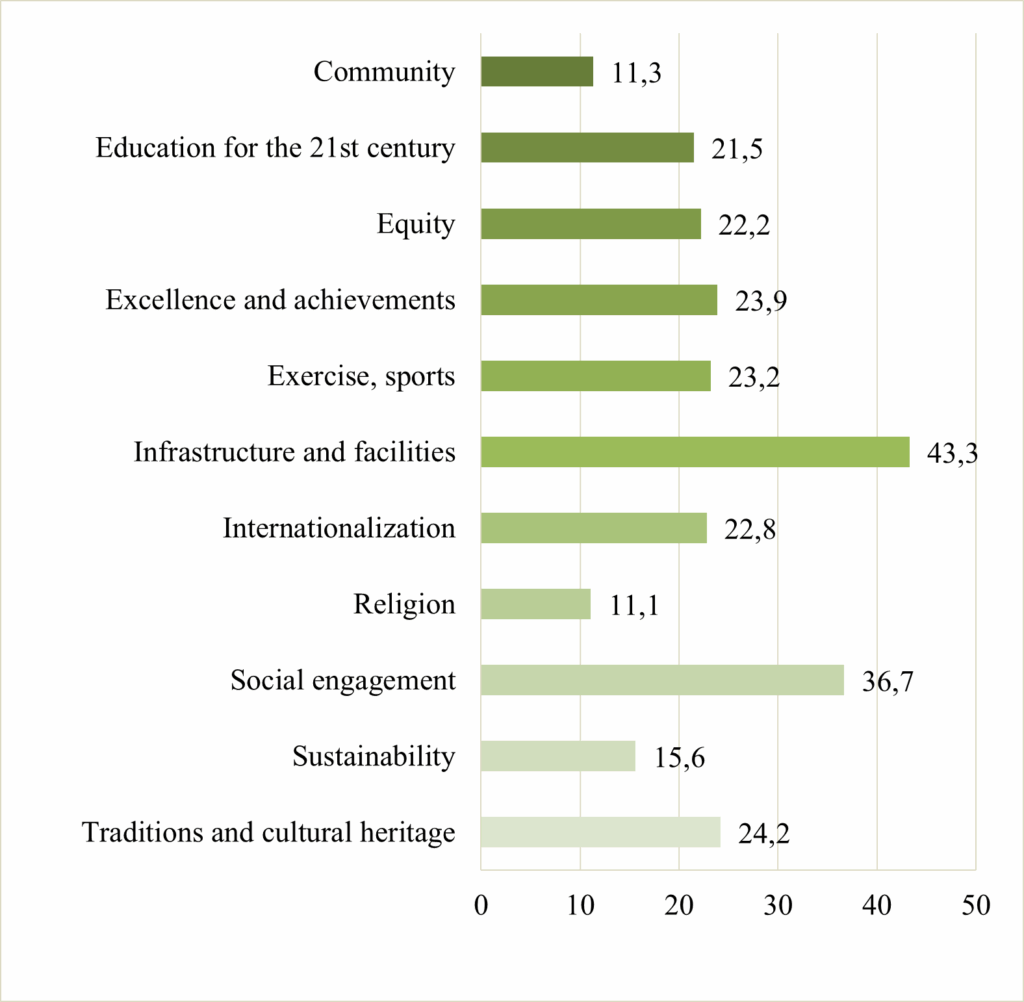

Figure 6 illustrates the previously mentioned results. Regarding student composition, the “Infrastructure and Facilities” value dimension shows the most extensive range, with a difference of 43.3 percentage points between the cluster with the lowest and the cluster with the highest relative frequency of this dimension in the narrative texts. Similarly, the “Social Engagement” value dimension also shows considerable variability. Notably, this dimension appears in less than 40 percent of the analyzed texts overall, and the nearly 40 percentage point range indicates that the emphasis on social engagement varies significantly depending on student composition. In contrast, the “Religion” and “Community” value dimensions appear with similar frequency across the student composition clusters. The relative frequencies revealed that these dimensions are present in most texts, and as shown in Figure 6, they are consistently emphasized regardless of student composition.

The following table (Table 1) provides a detailed overview of the proportions in which each value dimension is present across the groups categorized by student composition. As the table shows, regional centers with favorable backgrounds (N=23) tend to highlight “Religion” (95.7%), “Community” (69.6%) and “Excellence and achievements” (69.6%), while “Social engagement” (39.1%) and “Exercise, sports” (43.5%) value dimensions appear to a lesser extent. In the case of institutions facing combined social and educational disadvantages (N=9) “Religion” (88.9%) and “Excellence and achievements” (88.9%) are also the most common value dimensions, but “Equity” (33.3%) and “Infrastructure and facilities” (33.3%) are present in the most minor proportion of the analyzed texts – the relative frequency of “Infrastructure and facilities” is also much lower than in the other clusters’ texts. It is also important to highlight that in the texts of institutions facing combined social and educational disadvantages, the “Social engagement” value dimension is present at a much higher rate (66.7%) than in the other clusters’ texts (30-39%). Likewise, the relative frequency of “Internalization” (77.8%) in the texts of the previously mentioned cluster is also much higher than in the texts of the other clusters. The “Religion” value dimension is present in 91.5% of the analyzed texts from local institutions with favorable backgrounds (N=47). However, in the case of this cluster, the “Traditions and cultural heritage” value dimension (89.4%) is the second most commonly occurring value dimension. “Education for the 21st century” (36.2%) and “Social engagement” (38.3%) are the less common value dimensions in the texts of the previously mentioned cluster. The same preference can be observed in the case of the institutions with a high concentration

of behavioral, learning, and developmental issues (N=20): the “Religion” (100%) and “Traditions and cultural heritage” (80%) value dimensions appear in the most significant proportion of the texts. In comparison, “Equity” and “Social engagement” value dimensions can be found in 30-30% of the texts.

Figure 6.

Range between lowest and highest relative frequency among student composition clusters (N=99; percentage points)

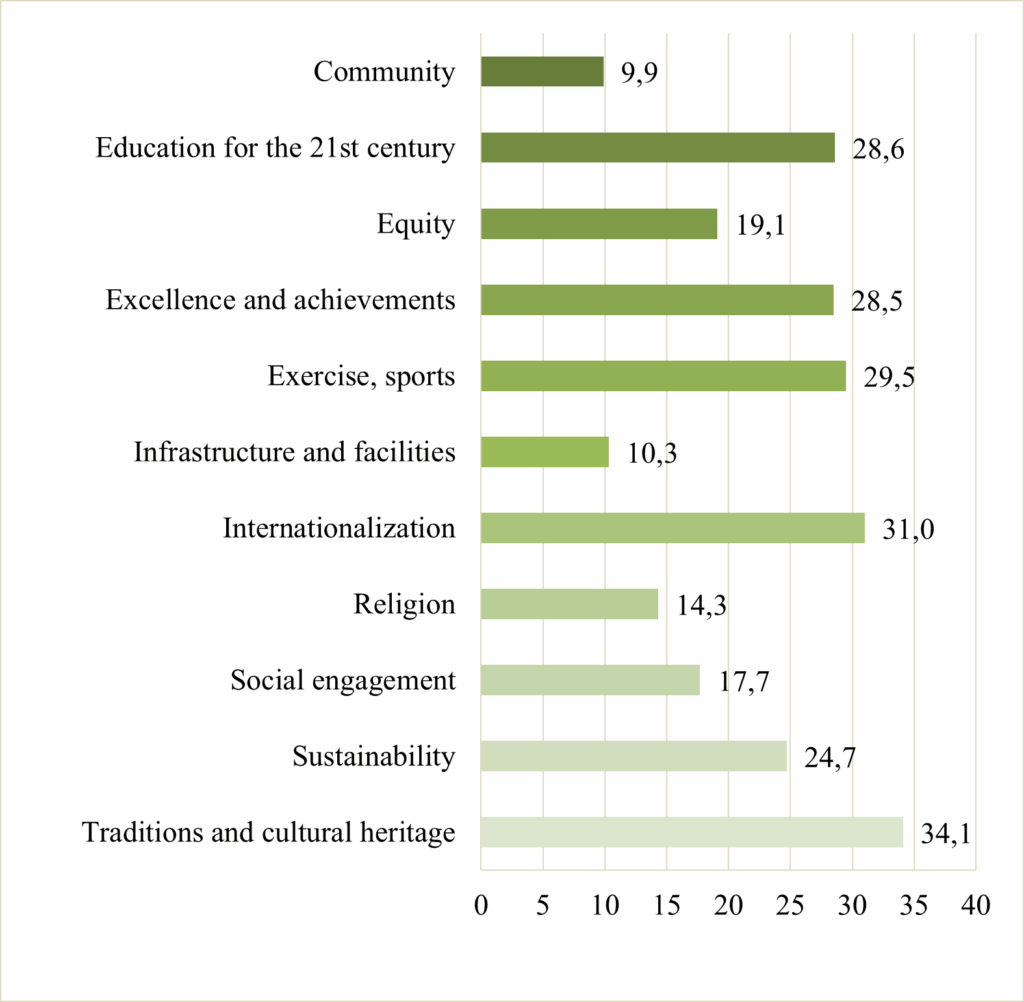

In terms of institutional structure, the distribution of value dimensions reveals a somewhat different pattern, with some dimensions appearing with similar frequency across clusters and others exhibiting greater variability in relative frequency values among clusters. The widest range in relative frequency by institutional structure can be observed for the “Traditions and Cultural Heritage” and “Internationalization” value dimensions. The former is present in 80.8 percent of the narrative texts overall. However, the 34.1 percentage point range indicates that, depending on institutional structure, it can appear at a much higher or significantly lower frequency as well. Similar to the findings based on student composition, the “Religion” and “Community” value dimensions also appear with relatively consistent frequency across institutional structure clusters. Additionally, communication regarding infrastructure and facilities does not show significant variation based on institutional structure (see Figure 7.).

Table 1.

Relative frequency of value dimensions among student composition clusters (N=99; %)

| Regional centers with favorable backgrounds (N=23) | Institutions facing combined social and educational disadvantages (N=9) | Local institutions with favorable backgrounds (N=47) | Institutions with a high concentration of behavioral, learning, and developmental issues (N=20) | |

| Community | 69,6% | 77,8% | 80,9% | 70,0% |

| Education for the 21st century | 56,5% | 55,6% | 36,2% | 35,0% |

| Equity | 52,2% | 33,3% | 42,6% | 30,0% |

| Excellence and achievements | 69,6% | 88,9% | 85,1% | 65,0% |

| Exercise, sports | 43,5% | 66,7% | 61,7% | 50,0% |

| Infrastructure and facilities | 56,5% | 33,3% | 76,6% | 65,0% |

| Internationalization | 56,5% | 77,8% | 66,0% | 55,0% |

| Religion | 95,7% | 88,9% | 91,5% | 100,0% |

| Social engagement | 39,1% | 66,7% | 38,3% | 30,0% |

| Sustainability | 47,8% | 44,4% | 57,4% | 60,0% |

| Traditions and cultural heritage | 65,2% | 77,8% | 89,4% | 80,0% |

The table below (Table 2) presents the proportion of analyzed texts in which the value dimensions are present, segmented by institutional structure. In the texts of small, exclusively primary education institutions (N=18), after the “Religion” value dimension (94.4%), the “Community” (77.8%) and “Infrastructure and facilities” (72.2%) value dimensions are most present. In comparison, the “Education for the 21st century” and “Social engagement” value dimensions appear in only 33.3% of the analyzed texts. The “Traditions and cultural heritage” value dimension is present in 61.1% of the small, exclusively primary education institutions’ texts, while in the other clusters’ texts it is between 80% and 95%. In the case of medium-sized, exclusively primary education institutions (N=45), after the “Religion” value dimension (95.6%), the “Traditions and cultural heritage” value dimension is present in the highest rate (82.2%) of the analyzed texts, while aside “Education for the 21st century” (35.6%), “Equity” (37.8%) is the other underrepresented value dimension. Large, exclusively primary education institutions (N=21) differ slightly, as the top two value dimensions are “Excellence and achievements” and “Traditions and cultural heritage”, which appear in 95.2% of the texts. The “Education for the 21st century” value dimension should also be mentioned, as it is present at a significantly higher rate (61.9%) in the texts of large, exclusively primary education institutions compared to the other clusters (33-47%). The “Social engagement” value dimension appears at the lowest rate (42.9%) in the texts of the previously mentioned cluster. Multi-purpose institutions (N=15) fit the pattern of the other clusters in terms of the most popular value dimensions. The value dimension that occurs in the lowest proportion of texts is “Social engagement” in this cluster as well; however, it should be emphasized that this proportion is the lowest among all clusters and value dimensions, at only 26.7%.

Figure 7.

Range between lowest and highest relative frequency among institutional structure clusters (N=99; percentage points)

Table 2.

Relative frequency of value dimensions among institutional structure clusters (N=99; %)

| Small, exclusively primary education institutions (N=18) | Medium-sized, exclusively primary education institutions (N=45) | Large, exclusively primary education institutions (N=21) | Multi-purpose institutions (N=15) | |

| Community | 77,8% | 71,1% | 81,0% | 80,0% |

| Education for the 21st century | 33,3% | 35,6% | 61,9% | 46,7% |

| Equity | 44,4% | 37,8% | 52,4% | 33,3% |

| Excellence and achievements | 66,7% | 75,6% | 95,2% | 73,3% |

| Exercise, sports | 55,6% | 48,9% | 76,2% | 46,7% |

| Infrastructure and facilities | 72,2% | 64,4% | 61,9% | 66,7% |

| Internationalization | 50,0% | 57,8% | 81,0% | 66,7% |

| Religion | 94,4% | 95,6% | 85,7% | 100,0% |

| Social engagement | 33,3% | 44,4% | 42,9% | 26,7% |

| Sustainability | 55,6% | 48,9% | 71,4% | 46,7% |

| Traditions and cultural heritage | 61,1% | 82,2% | 95,2% | 80,0% |

The following chapter summarizes the descriptive findings presented above, highlights the limitations of the study, and offers an outlook on potential directions for future research.

Summary

This study is descriptive in nature. It does not aim to uncover deeper casual relationships, nor is it suited for that purpose. Instead, it provides a cross-sectional snapshot of the value dimensions that appear on the websites and in the narrative texts of Reformed primary schools in Hungary. The results of the analysis enable the establishment of a ranking of the 11 examined value dimensions. Figure 8 below illustrates the ranking positions of each value dimension based on their relative frequency in narrative texts, their relative frequency in the menu structure, the relative frequency of prominent communication (i.e., joint occurrence in both narrative texts and menu structures), and the range of relative frequencies observed across background variable clusters within narrative texts. In all cases, a lower rank (starting from 1) corresponds to a lower value on the respective indicator. The figure clearly shows that “Religion” appears consistently and at a high rate across both the narrative texts of the relevant subpages and the menu structures of the websites, regardless of background variables. In contrast, while “Traditions and Cultural Heritages” also appears frequently overall, its prevalence varies depending on background factors. “Equity” and “Social Engagement” do not emerge as prominent themes, and the variation in their values across background variables is moderate. However, in the case of “Social Engagement,” it is noteworthy that its relative frequency by student composition shows an extensive range.

Figure 8.

Summary figure – Ranking of value dimensions according to different aspects of the analysis

As shown above, the results indicate that Reformed Church-run primary schools do not form a homogeneous group in terms of the values they communicate. The differences manifest as distinct value patterns, stemming from both structural characteristics and variations in student composition. However, the analysis highlights that intellectual, moral, and cultural core values—primarily religion, traditions, cultural heritage, excellence, and community—consistently occupy a central role in the self-representation of these schools, regardless of institutional background characteristics, albeit with varying emphasis. Based on student composition, the “Equity” value dimension should be highlighted, as it is less communicated overall. However, in the texts of institutions facing combined social and educational disadvantages, as well as those with a high concentration of behavioral, learning, and developmental issues, it appears at an even lower relative frequency than average. According to institutional structure, it can be stated that the value dimension “Social engagement” is communicated to a lesser extent, but significantly less by small, exclusively primary education institutions, and multi-purpose institutions. A similar observation can be made about the “Education for the 21st century” value dimension, which is less represented in the analyzed texts, particularly in the texts of small and medium-sized, exclusively primary education institutions.

It is also important to emphasize that as for now school websites represent the most easily accessible and institution-controlled source of information for parents navigating school choice. Unlike second-hand impressions gathered through word-of-mouth or open-day experiences, websites offer a non-mediated platform where schools can articulate their self-image, values, and educational philosophy directly. Despite this potential, the analysis revealed that many institutions either lack a functioning website or fail to use it as a tool to communicate their mission and value commitments. In some cases, an introductory text is available but makes no reference to core values, indicating that these schools do not fully leverage this strategic communication channel in a competitive educational environment.

The aim of the present research was to explore the communicated value dimensions. Based on the results, no specific communication strategy recommendations can be formulated for schools. However, the research provides a solid foundation for further, more in-depth studies through its findings regarding the existence of school websites, the publication of information, and the displayed value dimensions. Such future research could potentially link these aspects to school success or other characteristics, thereby enabling the identification of best practices and the formulation of more concrete recommendations. Based on the results, the research can be further developed along two main target groups: involving both parents and schools. This could help validate the preferred sources and platforms parents use to gather information, as well as the key drivers behind their decision-making processes. On the institutional side, it may also reveal the barriers to effective communication and support the assumption that limitations in local digital infrastructure and staff capacity may partially explain the absence or poor quality of online content.

References

- Abreu, Madalena (2006) The brand positioning and image of a religious organisation: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 11(2). 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.49

- Álvarez Herrero, Juan Francisco – Roig Vila, Rosabel (2019) The Websites of Schools. Analysis of the Current Situation in the Valencian Community. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 2020(50). 129–147. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.50.129–147

- Bacskai Katinka – Ceglédi Tímea (2023) Ugródeszka-e a református iskola a hátrányos helyzetű tanulóknak? Reziliens diákok a református oktatási rendszerben. Collegium Doctorum, 18(2). 282–291.

- Bacskai Katinka (2007) Iskolai légkörvizsgálat nyolc debreceni gimnáziumban. Educatio, 2007/2. 323–330.

- Bacskai Katinka (2008) Református iskolák tanárai. Magyar Pedagógia, 108(4). 359–378.

- Bacskai Katinka (2009) Teachers of Reformed Schools in Hungary. Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, 4(1). 15–22.

- Berényi Eszter – Berkovits Balázs – Erőss Gábor (2005) Iskolaválasztás az óvodában: A korai szelekció gyakorlata. Educatio, 2005/4. 805–824.

- Cucchiara, Maia B. – Horvat, Erin M. (2014) Choosing selves: the salience of parental identity in the school choice process. Journal of Education Policy, 29(4). 486–509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.849760

- Dimopoulos, Kostas – Tsami, Maria (2018) Greek Primary School Websites: The Construction of Institutional Identities in a Highly Centralized System. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 17(4). 397–421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2017.1326147

- Drahos Péter (1992) Katolikus iskolák az államosítás után. Educatio, 1(1). 46–64.

- Gilleece, Lorraine – Eivers, Eemer (2018) Primary school websites in Ireland: how are they used to inform and involve parents? Irish Educational Studies, 37(4). 411–430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2018.1498366

- Horváth Attila (2016) A szovjet típusú diktatúra oktatáspolitikája Magyarországon. Polgári Szemle, 12(1–3). 94–114.

- Jabbar, Huriya – Lenhoff, Sarah W. (2019) Parent decision-making and school choice. In: Berends, Mark – Primus, Anna – Springer, Matthew G. (2019 Eds.) Handbook of Research on School Choice (2nd ed.). New York, Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781351210447-25

- Juravle, Ariadna-Ioana – Sasu, Constantin – Spătaru, Geanina C. (2016) Religious Marketing. SEA – Practical Application of Science, 4(11). 335–340.

- Kodácsy-Simon Eszter (2015) Miért tart fenn az egyház iskolát? In: Szabó Lajos (2015 szerk.) Teológia és oktatás. Budapest, Luther Kiadó. 184–204.

- Kopp Erika (2005) Református középiskolák identitása. Értékek és identitásmodellek a tanárok és diákok véleménye tükrében. Educatio, 2005/3. 554–572.

- Major Enikő – Bacskai Katinka – Engler Ágnes (2022) Nevelési értékpreferenciák az állami és egyházi iskolákban. Educatio, 31(3). 479–488.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1556/2063.31.2022.3.9 - Ministry of Human Capacities (2020) Statistical Yearbook of Public Education 2017/2018. Budapest, Ministry of Human Capacities.

- Neumann Eszter – Berényi Eszter (2019) Roma tanulók a református általános iskolák rendszerében. Iskolakultúra, 29(7). 73–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.14232/ISKKULT.2019.7.73

- Neumann Eszter (2025) How churches make education policy: the churchification of Hungarian education and the social question under religious populism. Religion, State & Society, 53(2). 97–116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09637494.2024.2399452

- Papp Z. Attila – Neumann Eszter (2021) Education of Roma and educational resilience in Hungary. Social and Economic Vulnerability of Roma People, 79.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52588-0_6 - Papp Z. Attila (2022) Mérve vagyon: Az egyházi iskolák néhány oktatásstatisztikai jellemzője. Educatio, 31(3). 356–373. http://dx.doi.org/10.1556/2063.31.2022.3.2

- Payne, Adrian – Frow, Pennie (2014) Developing superior value propositions: A strategic marketing imperative. Journal of Service Management, 25(2). 213–227.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-01-2014-0036 - Péteri Gábor – Szilágyi Bernadett (2022) Egyházak a köznevelési költségvetésben. Educatio, 31(3). 461–478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1556/2063.31.2022.3.8

- Porter, Michael E. (1985) Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1556/2063.31.2022.3.8

- Pusztai Gabriella – Rosta Gergely (2023) Does Home or School Matter More? The Effect of Family and Institutional Socialization on Religiosity: The Case of Hungarian Youth. Education Sciences, 13(12). 1209. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121209

- Tardío-Crespo, Víctor – Álvarez-Álvarez, Carmen (2018) Análisis de las Páginas Web de los Centros Públicos de Educación Secundaria de Cantabria (España). REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 16(3). 49–65.

https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2018.16.3.003 - Varga Júlia (2024 szerk.) A közoktatás indikátorrendszere 2023. Budapest, HUN-REN Közgazdaság- és Regionális Tudományi Kutatóközpont, Közgazdaság-tudományi Intézet.

- Wilkinson, Jacqueline (2020) The Rural and Small Church of Ireland Primary School: The Use of School Websites to Define School Ethos. Rural and Small School Journal, 4(1). 230–247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14704994.2019.1649822

- Wrenn, Bruce (2010) Religious marketing is different. Services Marketing Quarterly, 32(1). 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2011.533095