Mediating Synodality

Stakeholders and Social Media Engagement in the Hungarian-speaking Catholic Sphere

Hivatkozás:

Glózer Rita & Hornyák Miklós (2025). Mediating Synodality. Jel-Kép: Kommunikáció, Közvélemény, Média, (2.) 3-31. 10.20520/JEL-KEP.2025.2.3

Abstract

This article explores how the synodal process initiated by Pope Francis is communicated, mediated, and discussed within Hungarian-speaking Catholic communities on Facebook. Using text mining techniques and manual content analysis, the study identifies the key institutional and individual stakeholders involved in the digital discourse on synodality. A total of 491 Facebook posts from 44 public accounts were analysed, with a focus on content types, stakeholder roles, geographical distribution, and temporal patterns. The findings reveal that ecclesiastical media outlets, transnational actors, and Greek Catholic representatives play a disproportionately active role in shaping the online narrative. While most of the content consists of reposted institutional news, a smaller set of original posts reflects personal involvement and community-oriented messaging. The study also highlights the uneven communication engagement of diocesan centres, and the dominance of content linked to central synodal events in Rome. By analysing communication patterns, participation strategies, and the spatial-temporal structure of the discourse, this article contributes to a better understanding of how synodality is represented and enacted in digital Catholic spheres.

Keywords

Following the completion of this manuscript, His Holiness Pope Francis passed away. We respectfully dedicate our study to his honourable memory.

Introduction

On 9 October 2021, for the fiftieth anniversary of the institution of the Synod of Bishops, Pope Francis proclaimed the Synod on Synodality, a process aimed at promoting the fundamental renewal of the Roman Catholic Church. According to the Pope’s opening address1, the synodal journey is structured around three key pillars: communion, participation, and mission. While communion reflects the very nature of the Church, mission pertains to its responsibility to proclaim „the kingdom of God among all peoples.” To achieve these objectives, broad participation is essential, mainly through the active involvement of the laity, members of local churches, and individuals at various levels of the ecclesial hierarchy. Given this vision and the complexity of the synodal process, effective communication plays a crucial role in multiple dimensions.

First, the call to the synod and its core ideas and messages must be disseminated widely among Church members. Second, synodality is fundamentally a process of collective discernment, requiring participants to engage in dialogue, listen to one another, and reflect together in the Holy Spirit. This inclusive communication is vital to ensuring broad participation, a key factor in the success of the synodal process. Third, the outcomes of the synod must be communicated to the wider public, necessitating strategic and transparent dissemination efforts. In the contemporary media landscape, digital platforms and online channels offer significant opportunities to facilitate and support the synodal journey.

The relevant literature also emphasises the crucial role of communication in the synodal process. One frequently raised question is what narratives and storytelling strategies the media should employ to present the public with a truly authentic portrayal of the Synod’s events and outcomes. Social media’s opportunities for fostering productive public conversation in the synodal process have also been widely discussed. In the era of participatory culture (Jenkins 2006), digital media platforms enable and encourage individuals to actively engage in producing, disseminating, and discussing information and narratives. In principle, this form of online communication has the potential to mediatise the synodal process effectively.

Since the synodal documents place a strong emphasis on locality and local communities (Mattei 2024), it is essential to consider how the renewal process is received and implemented at the local level. This study explores the role of online communication in this process, focusing specifically on how the synodal journey has been mediated within the Hungarian Catholic Church and the Hungarian-speaking public sphere. Our research primarily involves collecting and analysing synod-related content shared on Hungarian-speaking social media channels between 2021 and 2025, with a particular focus on Facebook. The main objective is to identify the key actors involved in the dissemination of social media content on this topic. By selecting the most frequently used public channels for sharing information about synodality in the Hungarian context, we aim to pinpoint the initiators and drivers of the synodal process. Our paper also examines the extent and intensity of participation by ecclesiastical institutions, dioceses, parishes, clergy, independent theologians, and laypeople in content dissemination and communication.

Tradition and renewal

The term ‘synod’ is composed of the words sún (with) and the noun hodós (path), referring to a communal journey undertaken by God’s people, symbolising their collective pilgrimage; thus, it is conceptually linked to communion (Brazal 2024: 95). As Brazal points out, synodality can be understood as a “constitutive dimension of church that embodies this communion among the members in their journey together, assembly gathering, and mission. Synodality is therefore not just a form of government of the church but a way of being church” (Brazal 2024: 96). Moreover, synodality as a concept with a theological foundation („a way of being church”) has been established in the institution of the Synod of Bishops throughout the history of the Church. This permanent council of bishops advises and informs the Pope and, in certain circumstances, holds decision-making authority.

According to Camelli (2024), the church’s synodal nature is already evident in the Gospels in the several calls, sendings and sharings in Jesus’ missions that he addresses to those who seek to follow him. Camelli interprets all the referenced Scripture passages (Mark 3:13-15, Luke 5:1-11, Matt 10:1) as illustrating the co-responsibility of Jesus’ followers in the mission, a central element of the Church’s identity. Drawing on Jean-Paul Adet, Canelli identifies three interconnected characteristics of the Church: a community, a structured institution, and a movement, the latter being manifested in its mission. Accordingly, synodality – along with the active participation and co-responsibility of the laity – has deep historical roots in the Roman Catholic Church (Cameli 2024). However, significant obstacles hinder both laity and clergy from embracing synodal renewal and conversion (Mattei 2024), notably clericalism and a “pervasive mindset among Catholic people that leads them to view the Church as an institution that provides resources they can consume” (Cameli 2024).

The structural model and the meaning of synodality have been extended by Pope Francis in recent years, both through his teachings and the increasingly participatory nature of the Synod of Bishops since 2014 (Brazal 2024). This extension includes the mandatory consultation of the faithful at the beginning of the process and the reception of the conclusion by the Church, as the People of God, at the end of the implementation phase. Furthermore, the range of participants was extended to include non-bishops and non-voting guests, as well as competent higher education institutions and various groups, so that they could submit their views. Compared to previous eras, the method of operation of the synod since the consecration of Pope Francis has been increasingly based on listening and discussion. All these developments clearly demonstrate the Pope’s trust towards maximum inclusion and participation “even of the excluded and those who have left the church” (Brazal 2024: 100).

Synodality, communication, and media

From the perspective of phenomenological sociology (Schütz 1932, Berger and Luckmann 1966), the social world is a constructed reality shaped and sustained through communication. Social institutions, roles, and meanings emerge from communicative processes. In communities and social institutions united by shared values and beliefs, the exchange of information, mutual listening, and open dialogue play a particularly vital role in fostering cohesion and continuity. Similarly, theories of organisational communication and culture highlight communication channels, forms, strategies, and dynamics as powerful instruments for the functioning, sustainability, and development of organisations (Miller 2012).

Synodality, as a constitutive principle and praxis of the Church as an institution, is inherently linked to communication – especially in processes of opinion exchange, mutual listening, consultation, negotiation, and decision-making. As Father Ihejirika, a Catholic priest and professor of communication and media studies in Nigeria, highlights, many of the key themes of the Synod – such as synodality itself, communion, and participation – are „predominantly communicative concepts” (Ihejirika 2024). Consistent with this view, the importance of communal discernment and the active involvement of laypeople is frequently emphasized in both official Synod documents and the secondary literature (Cameli 2024). All these forms of communication allow laypeople to join conversations, discuss current issues and offer advice, as described in the Second Vatican Council’s constitution, Lumen Gentium. However, existing participatory bodies provide laypeople limited advisory participation opportunities, particularly in decision-making (Mattei 2024). Thus, Zaccaria (2024) argues that the synodal process necessitates a profound reform of the Church’s decision-making structures to maintain a balance between “the common dignity of all the baptised and the value of the hierarchical structure of the church” (Zaccaria 2024: 15). The broadening of decision-making and lay participation emerged as a central issue during the Synod’s preparatory phase, reinforcing the idea that the Church must “move towards joint decision-making procedures involving both clergy and laity” (Zaccaria 2024: 15).

This shift is grounded in biblical and theological arguments emphasising co-responsibility (Cameli 2024, Zaccaria 2024), which reflects the fundamental equity of all the baptised. As a core tenet of the Christian faith, this equity establishes not only their equal dignity but also their shared responsibility in ecclesial life. Importantly, as Zaccaria highlights, this concept does not undermine the hierarchical constitution of the Church but rather necessitates that authority be exercised in agreement with the community in a synodal manner. Such an approach fosters lay participation beyond mere consultation, advocating for their meaningful inclusion in joint decision-making processes. In his study, Zaccaria differentiates between various levels of lay involvement in church leadership, ranging from the passive reception of information about decisions and their rationale to more active forms, such as consultation and dialogue, culminating in the highest level of participation: joint decision-making. According to him, shared responsibility and joint decision-making can be expressed by reforming the existing participation bodies or establishing new participation structures with deliberative power.

New communication methods within the Church for synodal renewal can only succeed if the process becomes widely known among the faithful and broader society. In other words, the success of synodal transformation largely depends on how modern mass media – exceptionally networked and social media – engage with it. The scale, reach, content, and quality of media coverage are all critical factors. In this context, Ihejirika draws attention to the importance of storytelling, emphasizing that stories “are constructed from socio-historical artefacts, both real and imaginary” and are “woven together to form meaningful narrative” (Ihejirika 2024). Storytelling is a communal activity that brings people together and strengthens social bonds – “an essential fabric of social life,” as he puts it. Today’s storytellers are journalists and all those who communicate through media. For this reason, he argues, Catholic journalists must go beyond the usual sensationalist patterns of mainstream media and present stories – including those related to the Synod – in ways that can strengthen and build communities.

However, the relationship between the Synod and the media should go beyond mere information dissemination. Social and participatory media provide the Church – including local communities, dioceses, parishes, church movements, ecclesial educational institutions, and religious orders – opportunities for dialogue. They enable members to listen to one another’s views, discuss key Synodal issues, and organise and publicise meetings and events.

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, the most popular social networks, and YouTube, the most used video sharing platform, are widely considered scenes for the “participatory culture” of the 21st century. Jenkins (2006), Bruns (2008), Burgess and Green (2009) and others point out that, in the age of the read-write internet, the one-way communication and expert paradigm associated with the early internet is replaced by not only a two-way communication but also the active involvement of users in the production and distribution of media content. The advent of a “participatory culture” in the media in the early 2000s promised unlimited participation of users, providing them opportunities and arenas to express their ideas creatively while collaborating and supporting each other. User-generated content and online communities played crucial roles in this era. However, less democratic and participatory tendencies have emerged soon, including the monetisation of amateur content, unnoticed exploitation (Fuchs 2014) of the users who create and spread content (unpaid work) and various abuses (data collection, etc.) by the increasingly powerful big media platforms (Poell – van Dijk 2018). Today, we are aware not only of the benefits and advantages of participatory culture but also of its drawbacks. At the same time, the participatory spirit, brought about by the proliferation of social media and the active participation and contribution of users, is also being spread to other areas of social life and everyday life. In the field of social research, new participatory research methods – such as Participatory Action Research (PAR) – have been developed and become widely adopted. Similar trends can be observed in education, the arts, and even marketing, where participatory approaches such as participatory theatre, participatory art, participatory museums, and participatory marketing have gained ground.

In summary, the synodal transformation and functioning of the Church require both new interpersonal and mediated forms of communication to prevent the reduction of decision-making to simple majority voting, which is unsuited to the Church’s nature and mission. As Zaccaria points out, “the content of faith is received and transmitted (1Cor 15:3; 11:23) and not the outcome of a decision-making process” (2024: 15).

This global trend, however, is shaped by local contexts and actor-specific practices. Communication within and about the synodal process in Hungary is embedded in the broader communication strategies and media usage practices of the Hungarian Catholic Church, as well as those of religious communities and other faith-based stakeholders. In recent years, academic interest in this complex phenomenon has grown, with a growing body of literature addressing the digital media practices of churches and religious communities (Andok 2023a, Andok 2023b, Radetzky 2023), the forced digitalisation of ecclesiastic communication during the COVID-19 pandemic (Andok 2021), and the mapping and analysis of religious content creators on digital platforms in Hungary (Andok, Páprádi-Szilczl, and Radetzky 2023). To date, no scholarly work has specifically addressed the communicative and media-related aspects of the synodal process in the Hungarian context. This paper seeks to fill this gap by contributing to the study of social media communication by religious stakeholders in Hungary and the mediatization of synodality.

Methodology and data

To ensure a comprehensive investigation of the most actively engaged actors in the public discourse on synodal themes within the Hungarian-speaking social media space, we conducted a systematic social media analysis. For data collection, we applied text mining techniques. In the first phase of data collection, we focused on the two most recent full years of the synodal process (2023 and 2024), which began in 2021. This decision was based on the assumption that by this stage, the primary channels for discussing and mediating the synodal process on social media would already have been established. Our social media data collection targeted content posted by public accounts on the social networking platform Facebook, which was selected due to its popularity among Hungarian users. The number of Facebook users in Hungary amounted to 7.11 million as of November 2024, making Facebook the most widely used social media platform in the country2. We also considered its interactive affordances, which play a key role in shaping online discourse.

The data collection was not limited to actors based in Hungary but it was extended to Hungarian-speaking individuals and institutions beyond the country’s borders, as they also play a significant role in the discourse under study through the production and dissemination of Hungarian-language media content. Notably, substantial Hungarian-speaking minorities reside in the neighbouring countries of Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Croatia, and Ukraine, with smaller communities in Austria and Slovenia (Bárdi, Fedinecz and Szarka 2008). Additionally, substantial Hungarian diaspora communities exist in Western Europe and beyond. As Papp Z. et al. (2020: 295) pointed out, telecommunication has undergone advancements that enable individuals who relocate and settle abroad to remain virtually connected to the society of their country of origin. Their “transnational” way of life, as well as frequent cross-border interactions and collaborations among ethnic Hungarian communities and institutions, justify considering them as part of a broader public sphere in terms of media coverage.

Our data collection methodology is based on text mining in the field of data science. The goal of text mining is similar to data mining; it seeks to uncover patterns but operates on unstructured data such as documents, articles, text streams, and news. This pattern mining is based on the use of statistical methods, artificial intelligence applications, and neural networks, among others (Tikk 2007, Sebők et al. 2021).

In contrast to numerical data, language dependency poses a significant challenge with these text-based inputs, because these texts are written in natural languages (e.g. Hungarian, English). To address this problem, semantic and taxonomic analysis of the input can be an integral part of text mining. In our study, we used algorithms (HuSpacy) adapted to the specificities of the Hungarian language by a research team led by György Orosz, which provided the possibility to connect to standard text mining methods (Spacy, NLTK) (Orosz et al. 2023).

The prerequisite for text mining is an existing text base (corpus), on which it is possible to perform analyses after various pre-processing and cleaning operations. Thus, the first step of our research is the production of this corpus, for which we carried out a textual content extraction of the web pages. The algorithmic process is shown in Algorithm (1) (see Figure 1).

Using this method, 100 Facebook posts were included in the text corpus. The first 100 Facebook posts containing the terms ‘synod’ or similar synonyms published on Facebook since 2023 were selected. This was provided by Facebook’s internal search engine and sorted by relevance. The posts were processed with the help of the ESUIT browser extension (https://esuit.dev/), which made not only the text of the Facebook posts but also the reactions to them available for later analysis. It is worth highlighting the difficulties encountered during data acquisition, which were due to restrictions on access to social media data and required exploring alternative solutions3.

Figure 1

Algorithm used for the creation of the synodal corpus

Algorithm 1: Creating the synodic corpus

Input: accessibility of N text (URLN)For each URLi (i = 1,2,...N):Download the webpage (URLs) including HTML code Pi)

Extract text content by removing HTML elements from Pi (Ci)

Text preprocessing steps:

Tokenize text into words

Remove special tokens: email, numbers, symbols

Remove stopwords

Apply stemming

Handling bigramsEnd ForOutput: Text corpus consisting of N cleaned texts corpusThe Facebook content initially extracted through text mining methods was manually reviewed to filter out items unrelated to the current synodal process (e.g., content referring to previous synods). The cleaned dataset was then used to identify the relevant Facebook accounts. In the next step, each of these accounts was examined individually. Using Facebook’s internal search function, we retrieved all posts containing the keywords “synod” and “synodality” for each account (without any time constraints). This procedure yielded a substantially larger dataset of content related to the synod, supplementing the original corpus of 100 posts. A second round of data cleaning was conducted to remove irrelevant entries. As a result, 491 relevant Facebook posts were included in the final sample. This process also extended the data collection timeframe, which ultimately covered the period from 21 May 2021 to 15 March 2025.

It is essential to note the limitations of this two-phase data collection process. The original sample of 100 posts generated algorithmically is not representative, and since the additional manual data collection was based on this initial sample, the extended dataset is not representative either. Nonetheless, these first 100 contents likely reflect a realistic cross-section of the key stakeholders participating in the online discourse on the Synod among the Hungarian-speaking community. Despite the non-representative nature of the data, in-depth analysis of this diverse sample allows us to observe differences in the activity levels and communication frequency of various actor types, and to identify broader patterns in the digital mediation of synodal themes.

During the analysis phase, the 491 posts were coded based on the following characteristics: (1) type of content (text-only post, photo without text, or video), (2) origin of content (self-generated or re-shared), (3) name of the publishing account, (4) type of account maintainer or stakeholder (as detailed below), (5) affiliation of the maintainer or stakeholder (domestic, diaspora, or Vatican-based), (6) associated location, if specified, and (7) publication date. Due to scope limitations, the analysis did not extend to the textual content of the posts or the photos and videos shared. However, a detailed content analysis is planned for a later stage of the research, which will allow for exploring the thematic focus, key issues, stylistic features, and communi-cative strategies characterising the Hungarian-language social media discourse on the Synod.

Findings

Stakeholders involved in the mediatization of the synod

It is essential to highlight that the 491 Facebook entries vary significantly in the depth and detail they address synodal and synodic transformation. Some posts – such as the more extended summaries shared by the Vatican News Facebook account – include only brief reflections from Pope Francis on the synodal process. In contrast, other posts offer in-depth coverage of the deliberations taking place in Rome, often complemented by extensive content related to local events within the synodal process. The collected content spans the period from 21 May 2021 to 22 March 2025, which defines the timeframe of our analysis.

The social media content examined in this study originated from a total of 44 distinct Facebook accounts. One of the central aims of the research was to identify the individual and institutional actors who contributed to the Hungarian-language discourse on the Synod via Facebook. To address this question, we categorised the 44 accounts based on their owners’ institutional background and status. These content owners function as stakeholders in shaping the mediatisation and media portrayal of the synodal process.

Ten account types were then identified through inductive coding. These were defined based on the hierarchical level or territorial unit of the ecclesiastical institution to which each actor belongs, or by their affiliation with church-run or church-affiliated institutions, organisations, or movements. Separate categories were established for individuals holding positions within church institutions, members of religious orders, and private individuals with public profiles who engaged with the topic on the one hand, and for religious media outlets and publishers on the other hand. This typology aimed to identify relevant actor groups, organisational levels, institutional types, and other key stakeholders within the Hungarian-speaking Catholic community and institutional system who considered it essential to address the Synod and its themes through social media channels. These individuals and institutions may play a pivotal role in shaping the future trajectory of the Catholic Church’s synodal transformation by informing believers and interested audiences and using the participatory opportunities offered by social media to engage them in the synodal process. Table 1 (see in Appendix) provides a brief overview of the identified stakeholders.

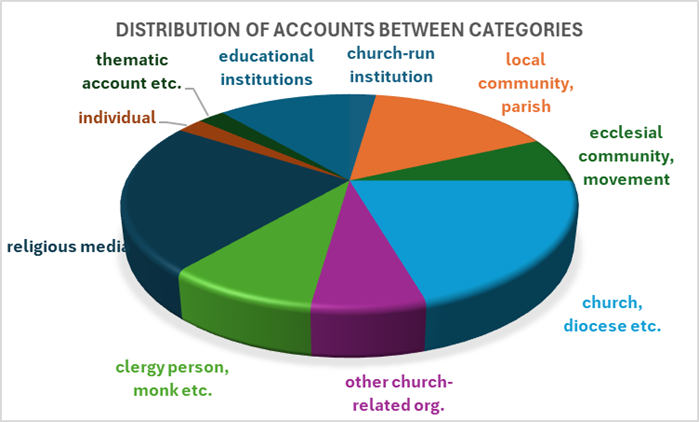

The stakeholders participated in the distribution of content related to the Synod on Synodality to varying degrees. First and foremost, it is important to highlight that the stakeholder types identified during the coding encompass differing numbers of particular stakeholders (see Figure 2). Religious media institutions – such as magazines, news portals, television and radio stations, and publishing houses – are the most represented in the sample, with ten Facebook accounts. Unsurprisingly, public communication and content distribution via social media are inherent to the operations of media outlets. The data reflect the activity and engagement levels of these actors.

Slightly behind in numbers, nine Facebook accounts are associated with institutions constituting the hierarchical and regional structures of the Church: the Hungarian Catholic Church, various dioceses, and archdioceses. These organizational units play a key role in both the organization and the communication of the synodal process, as they are able to transmit information to the faithful and organize events that support participation. It is also from these levels of church hierarchy that individuals were selected to attend synodal gatherings in Rome as invited participants.

The third most represented group in terms of the number of Facebook accounts (seven) consists of the Church’s smaller, local units and communities – namely, parishes. One of the core messages of the Synod is that renewal must also occur at the local parish level, within local contexts. Therefore, informing and involving local communities – potentially through social media – is of particular importance.

In the middle range of the sample, we find smaller-scale or specialized ecclesiastical and educational institutions, movements, and individual church figures. Among the clergy included here are theologians and bishops who were invited participants in the synodal consultations held in Rome and who shared related information first-hand via their personal Facebook profiles. Finally, the sample also includes one Facebook account belonging to a private individual, one maintained by a church-affiliated institution, and one functioning as a thematic aggregator page (see in Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2

Amount and proportion of different types of stakeholders in the research sample (n=491)

| Category of the stakeholder | Number of accounts in the category | The ratio of the total accounts |

| religious media | 10 | 22,73 |

| church, diocese etc. | 9 | 20,45 |

| local community, parish | 7 | 15,91 |

| educational institutions | 5 | 11,36 |

| clergy person, monk etc. | 4 | 9,09 |

| other church-related org. | 3 | 6,82 |

| ecclesial community, movement | 3 | 6,82 |

| church-run institution | 1 | 2,27 |

| individual | 1 | 2,27 |

| thematic account etc. | 1 | 2,27 |

| Total | 44 | 100 |

Figure 2

Distribution of the accounts between categories

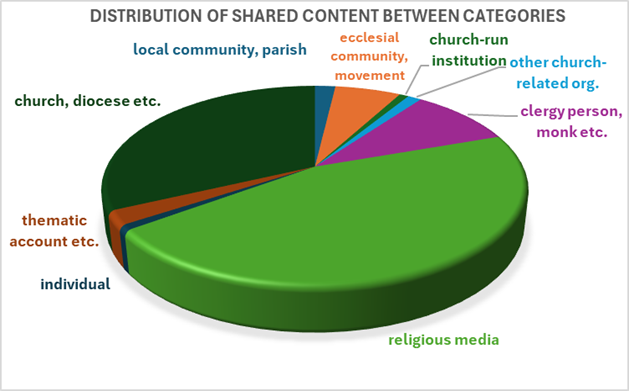

When examining the contentshared by the various stakeholder groups, a similar pattern emerges to what was previously described: religious and ecclesiastical media outlets occupy the leading position, accounting for more than 40% of all posts. These are followed by the Church’s larger territorial and organizational units, whose Facebook accounts are the source of approximately one-third of the content. The third most active group in terms of content sharing consists of individual church figures – such as theologians, bishops, and members of religious orders. In this case, the frequency of posting can be attributed to their personal involvement in and commitment to the synodal process. It can also be observed that, for the remaining stakeholder groups, the smaller the number of accounts within a given group, the lower the intensity of content sharing. These actors are thus less engaged in the public discussion of the Synod’s themes (see Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3

Amount and proportion of content shared by different types of stakeholders (n=491)

| Category of the stakeholder | Amount of content shared | Proportion of total content % |

| religious media | 215 | 43,79 |

| church, diocese etc. | 153 | 31,16 |

| clergy person, monk etc. | 46 | 9,37 |

| ecclesial community, movement | 29 | 5,91 |

| educational institutions | 15 | 3,05 |

| thematic account etc. | 10 | 2,04 |

| local community, parish | 9 | 1,83 |

| other church-related org. | 6 | 1,22 |

| church-run institution | 4 | 0,81 |

| individual | 4 | 0,81 |

| Total | 494 | 100 |

Figure 3

Distribution of shared content between categories

We also examined how the affiliation of various Hungarian-language Facebook accounts is distributed among domestic, cross-border Hungarian (i.e., diaspora), and Vatican-based entities involved in the dissemination of synod-related content (see Table 4 and Figure 4.). It can be stated that nearly 70% of the posts concerning the synodal transformation were published by stakeholders based in Hungary. At the same time, it is noteworthy that almost one-quarter of the content was shared by accounts affiliated with the Hungarian diaspora – primarily dioceses, institutions of higher education, and media outlets located outside Hungary’s borders. This indicates that, relative to their overall numbers, diaspora institutions participate in the Hungarian-language social media discourse on the Synod with a disproportionately high level of activity.

Table 4

Distribution of content by stakeholder affiliation (n=491)

| Stakeholders by affiliation | Amount of content | Proportion of total content % |

| Domestic | 339 | 69 |

| Diaspora | 118 | 24 |

| Vatican | 34 | 7 |

| Total | 491 | 100 |

Figure 4

Distribution of content by stakeholder affiliation

Content creation and dissemination show significant variation not only between stakeholder types but also within the individual groups themselves. Even among stakeholders of the same type, there can be considerable differences in terms of the frequency and intensity of content sharing. The table below (Table 5) presents the number of posts related to the Synod shared by individual Facebook accounts, broken down by stakeholder group.

Among the larger ecclesiastical units, Magyar Katolikus Egyház is matched in volume by Hajdúdorogi Főegyházmegye, with Nyíregyházi Egyházmegye trailing only slightly behind. Both are Greek Catholic dioceses in Hungary, suggesting that within the domestic Catholic community, Eastern rite parishes demonstrate a level of commitment and activity in amplifying and mediating the synodal process on social media that exceeds the average. The scale of their communication efforts is equivalent to that of the official account of the national Catholic Church.

Beyond these, only Váci Egyházmegye and Veszprémi Egyházmegye had content included in the sample. However, several Hungarian dioceses located beyond the country’s borders – such as Gyulafehérvári Katolikus Érsekség, Nagyváradi Egyházmegye, and Szabadkai Egyházmegye – also displayed notable levels of activity regarding the Synod on their respective Facebook accounts. According to our data, local parish communities are involved in the facilitation of the synodal journey on social media to a limited extent, with only a small number of posts – typically one or two – being shared per account.

Among ecclesial movements, the Fokoláré Mozgalom’s Új Város account stands out in terms of its activity. In the category of individual church figures, the personal Facebook account of theologian Csiszár Klára deserves special mention. An ethnic Hungarian from Transylvania and currently a faculty member at the University of Linz, she was among the women invited to participate in the synodal consultations in Rome. On her personal social media page, she actively shared updates and reflections on the synodal process.

Among church-affiliated or religious media outlets, Szemlélek Magazin published the highest number of synod-related materials. In addition, three domestic outlets – Vigilia, Magyar Kurír, and Zarándok.ma – and one diaspora news portal (Romkat.ro / Vasárnap) contributed a substantial amount of content to the discourse surrounding the Synod. It is also noteworthy that among the educational and higher education institutions that publicly addressed the Synod, only one – PPKE JÁK – is based in Hungary; the others are linked to the diaspora (BBTE, Kolozsvár) or the Vatican.

Table 5

Volume of content shared by the Facebook accounts under study

| Category of the stakeholder | FB account owner | Amount of content shared during the research period |

| church, diocese, archdiocese | ||

| Magyar Katolikus Egyház | 33 | |

| Hajdúdorogi Főegyházmegye | 33 | |

| Nyíregyházi Egyházmegye | 30 | |

| Váci Egyházmegye | 17 | |

| Gyulafehérvári Katolikus Érsekség | 15 | |

| Veszprémi Érsekség | 13 | |

| Nagyváradi Egyházmegye | 5 | |

| Olaszországi Magyar Katolikus Misszió | 5 | |

| Szabadkai Egyházmegye | 2 | |

| local community, parish | ||

| Bátaszéki Római Katolikus Plébánia | 2 | |

| Magyar Katolikusok Berlinben és Brandenburgban | 2 | |

| Kartali Szent Erzsébet Egyházközség | 1 | |

| Kapisztrán Szent János Kápolna | 1 | |

| Mária Neve Római Katolikus Plébánia Solt | 1 | |

| Pilisszántói Plébánia | 1 | |

| Szent Rita Templom | 1 | |

| ecclesial community, movement | ||

| Új Város | 18 | |

| Katolikus Hitoktatók | 8 | |

| Óföldeáki Zarándoklat | 3 | |

| church-run institution | ||

| Seminarium Incarnatæ Sapientiæ | 4 | |

| other church-related organisation | ||

| Egyházi Fejlesztők | 4 | |

| Beregszászi Pásztor Ferenc Közösségi és Zarándokház | 1 | |

| Militia Templi – Christi pauperum Militum Ordo | 1 | |

| clergy person, theologian, monk, monastic order | ||

| Csiszár Klára | 26 | |

| Kocsis Fülöp | 9 | |

| Jezsuiták | 7 | |

| Sajgó Szabolcs | 4 | |

| religious magazine, news site, TV, radio, news agency, publisher | ||

| Szemlélek | 54 | |

| Romkat.ro és Vasárnap | 42 | |

| Katolikus.ma és Zarándok.ma | 35 | |

| Vatican News | 27 | |

| Vigilia | 22 | |

| Magyar Kurir | 22 | |

| Mária Rádió | 7 | |

| Bizony Isten | 3 | |

| Bihari Napló | 2 | |

| Martinus Könyvkiadó | 1 | |

| individual | ||

| Józsa Emmi | 4 | |

| thematic account, collection page | ||

| Ferenc pápa beszédei, írásai (Tőzsér Endre) | 10 | |

| educational and higher education institutions | ||

| BBTE Vallás, Kultúra, Társadalom Doktori Iskola | 6 | |

| BBTE Római Katolikus Teológiai Kar | 4 | |

| Pápai Magyar Egyházi Intézet | 2 | |

| Pázmány jogi kar – PPKE ÁJK | 2 | |

| Xantus János Általános Iskola | 1 | |

Distribution of the content

The distribution of Facebook content types in the research sample reveals the dominance of post-type content that combines text and images, compared to content consisting solely of photos or videos. On Facebook, it is possible to share purely textual content without any visual elements (text-only posts), posts that combine text and visual content, images without any accompanying text, or video content. In the case of the latter, the Reels format has become particularly popular in recent years, allowing for the inclusion of music, audio tracks, AR effects, and other features.

Our research found that 91% of the sampled posts – 448 in total – contained both textual and visual components. The visual elements were most often photographs, though occasionally they included other types of graphics. In such content, the role of the text is often to provide context for the visual component, elaborate on it, offer explanations, interpretations, or clarifications. The textual component serves as a space for factual data, precise information, or calls to action directed at the audience. This pattern was also observed consistently in the cases examined. Beyond these, we identified 39 videos in the sample – mostly in the Reels format – accounting for nearly 8% of the total content. Video content enjoys high popularity on today’s social media platforms, as it is capable of conveying messages and information in an engaging, often entertaining or experiential format using a range of complex tools. As observed in some examples from our sample, videos allow for the inclusion of direct speech, making the message more personal and potentially more credible. Video formats tend to be significantly more popular among younger audiences than written text. We encountered only four instances – fewer than 1% of the sample – in which a photo was shared without any textual commentary or explanation. This low figure is understandable: without textual framing, such images lack context and are generally less effective in conveying specific information or calls to action.

The content in our sample can be divided into two main categories: posts that share newly created, original material produced by the account holder, and posts that redistribute existing content, such as website articles, videos, or posts from other Facebook accounts. The 173 original posts account for 35% of the entire sample. These original posts allow the account holders to formulate and shape their own messages according to their individual perspectives. This type of content thus offers an opportunity to express a personal voice, communicate individual opinions, and share relevant information, while also requiring media production skills and human resources.

Original content enables live reporting and on-site updates from various events where the account holder is personally present. Based on our findings, it can be generally stated that original content is typically shared by those who are directly involved in the synodal work – such as participants of synod-related events – or those who have a significant message to convey regarding the Synod. Some typical content-sharing strategies are clearly identifiable. For example, dioceses such as Váci Egyházmegye and Nagyváradi Egyházmegye, as well as the archdiocese Veszprémi Érsekség, typically published calls to action, event reports, questionnaires, and promoted Facebook events as original content.

Representatives of church media (e.g., radio stations, TV channels, the Vatican news agency, magazines, journals) predominantly shared self-produced content – which is entirely reasonable, as content creation is their core activity, and repurposing their material for social media does not pose a particular challenge. We also observe a significant amount of original content published by individuals closely affiliated with the Church – those who participated in synodal events as Hungarian delegates or as expert observers.

The number of reposted content in our sample is 318, making up 65% of the entire dataset – thus representing the overwhelming majority. This indicates that the stakeholders engaging

with the Synod on Facebook predominantly repost content that was created or originally published elsewhere. Such reposting can significantly increase the exposure of the original material. Among the accounts in our sample, the Magyar Katolikus Egyház, for instance, frequently shares content published elsewhere and has not posted any original material on the topic of the Synod. Instead, it exclusively reposts articles from church news agencies and press outlets, as well as content from websites dealing with the synodal process.

In the case of dioceses – such as Váci Egyházmegye, Nyíregyházi Egyházmegye, Szabadkai Egyházmegye, Hajdúdorogi Főegyházmegye, and the Gyulafehérvári Római Katolikus Érsekség – it can be observed that they primarily share longer articles originally published on their own websites. For these actors, the primary platform for information dissemination is their institutional website, and their social media pages serve mainly to promote that content and direct the social media audience to the website. A similar pattern can be observed among church-affiliated media outlets and ecclesial movements. In cases where the content published is not originally created for the Facebook account, these actors typically repost articles from their own websites. Although such posts are technically reposts, the content still conveys their own message, now amplified through social media – thus blurring the distinction between reposted and original content. Higher education institutions represented in the sample also typically share news from Catholic news portals and agencies, or articles from church-affiliated journals.

If we shift our perspective and focus not on the stakeholders who shared the content but on the reposted material itself, several characteristic trends can still be observed. The reposted content in our sample generally falls into three main categories, each with its own communicative logic and role in the broader synodal discourse. A significant portion of the reposted material consists of news content originating from ecclesiastical and other media sources, including platforms such as press.vatican.va, vaticannews.va, magyarkurir.hu, erdon.ro, romkat.ro, katolikusradio.hu, Erdély TV, and Telex. These posts typically provide concise, news-style updates, keeping followers informed about recent developments in the synodal process or related church events.

Another substantial group of reposted content comprises articles from Catholic magazines and cultural periodicals, such as Vigilia, Szemlélek, and megujul.hu. Unlike the news updates, these texts tend to offer more in-depth reflections, including analytical pieces, opinion essays, and interviews. They contribute to the interpretive layer of the synodal conversation by providing commentary, theological insight, or critical engagement with the process. A third prominent category includes content originally published on the websites of ecclesiastical institutions. These items frequently appear in reposts and serve as a bridge between institutional communication and the social media environment. In these cases, the reposting not only amplifies the visibility of the institutional message but also reinforces the integration of official church communication into the everyday digital practices of the faithful.

Through these acts of redistribution, the Facebook accounts and content of various stakeholders become interconnected within a kind of digital network, as reposting often involves formal or substantive referencing, recommending, or linking, thereby redirecting visitors from one social media account or platform to another.

Content across time and space

Some of the content we analysed could be clearly linked to a specific location or geographical area. During the coding process, we also recorded this spatial information by noting the name of the location – typically the headquarters or area of operation – whenever it was mentioned in the name or description of the account holder. Based on this, we were able to identify a total of 22 cities or regions. Given that one of the key aspects of the synodal transformation is its implementation at the level of local communities – through events and conversations taking place even at the parish level – we considered this geographical information to be valuable for mapping how synodal ideas are spreading across the Hungarian-speaking world.

The data show that, out of the 22 locations, 7 are regions or cities with a significant Hungarian minority population in Romania; one city (Berlin) serves as a centre for the Hungarian diaspora in Western Europe; and two locations (Rome and Vatican City) are the official venues of the Synod. The list below presents the 22 locations along with the number of related posts, while the accompanying word cloud (Figure 5) provides a visual illustration of this distribution.

Bátaszék (2), Beregszász (1), Berlin (2), Budapest (5), Csíkszereda (1), Debrecen (9), Erdély (8), Gyulafehérvár (19), Hajdúdorog (33), Kartalszenterzsébet (1), Kolozsvár (10), Nagyvárad (7), Nyíregyháza (30), Óföldeák (3), Pilisszántó (1), Róma (2), Solt (1), Szabadka (2), Szombathely (1), Vác (17), Veszprém (13), Vatikán (27)

Figure 5

Locations mentioned in posts or accounts by frequency of reference

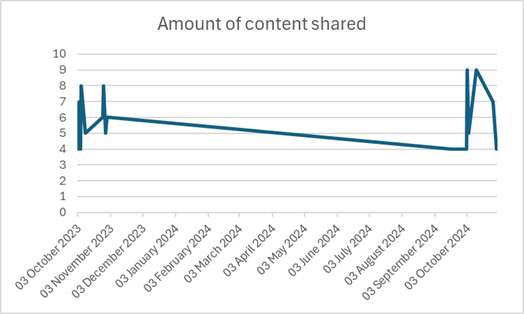

Analysing the temporal distribution of content related to the Synod helps identify which phases of the synodal process saw heightened activity in terms of national and regional implementation. It also reveals how the intensity of social media discourse corresponds to the official timeline of the Synod.

Our research findings indicate that the most intensive period of social media communication about the Synod began shortly after its official announcement and peaked in 2023. During that year, stakeholders shared 157 pieces of content, accounting for more than 30% of the entire sample. A slightly lower number – 146 posts – were published in 2024. These two years represent the most active phase of public Hungarian-language social media discourse related to the Synod (see Table 6 and Figure 6).

Table 6

Temporal distribution of the content analysed

| Year | Amount of media content shared | Proportion of total content % |

| 2021 | 57 | 11,61 |

| 2022 | 99 | 20,16 |

| 2023 | 157 | 31,97 |

| 2024 | 146 | 29,74 |

| 2025 | 22 | 4,48 |

| n. | 10 | 2,04 |

| Total | 491 | 100 |

Figure 6

Yearly distribution of media content

Within the examined timeframe of 1,394 days, only 297 days saw the publication of content related to the synodal transformation by the Facebook accounts included in our sample. The analysis identified 195 days on which only one such post was shared across all the accounts, and 66 days when two posts were published. There were 20 days with three posts, and two days each when six, seven, eight, and nine posts appeared.

The days with the highest content output occurred between October 3, 2023, and October 4, 2024. The most active days – those with nine posts – were October 3 and October 11, 2023. As the graph below (Figure 7) illustrates, significant spikes in posting activity occurred over short periods: October 3–12 and October 26–30 in 2023; and October 1–4, October 10–14, and around October 27 in 2024.

Figure 7

Distribution of shared content by date of publication (3 October 2023 – 4 October 2024)

These peaks align with the known schedule of the synodal assemblies in Rome: the first General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops began on October 4, 2023, and the second took place from October 2 to 27, 2024. Based on this temporal distribution, we can conclude that communication related to the synodal journey saw a noticeable surge during the general assemblies in Rome, whereas the intervening periods were Based on this, we may assume that the content appearing during these peak periods primarily reported on the synodal events taking place in Rome, rather than focusing on national or local synodal activities. Naturally, this assumption could only be confirmed or refuted through a detailed content analysis of the posts in question.

Discussion

During the data analysis, we encountered some non-obvious results that call for further explanation. One of the most striking findings was the active involvement of Hungarian ecclesiastical institutions and individuals located outside the borders of Hungary. A significant portion of both the analysed Facebook accounts and the shared content was linked to Hungarian diaspora communities. This can be partially explained by the fact that out of the seven Hungarian individuals personally invited by the Pope to take part in the synodal process, four are members of Hungarian minority communities outside Hungary (in Romania and Serbia). Among those representing Hungary at the synod was Péter Szabó, a Greek Catholic canon law professor and member of the Preparatory Theological Commission. Another expert participant was Klára Csiszár, a professor of pastoral theology born in Transylvania (Romania) and currently teaching at the Catholic Private University in Linz. The Roman Catholic community in Hungary was represented by Gábor Mohos, auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Esztergom-Budapest, while Fülöp Kocsis received an official invitation as the head of the Greek Catholic Church in Hungary. László Német, Archbishop of Belgrade (Serbia) and president of the International Episcopal Conference of Saints Cyril and Methodius, was also a full synodal member. Romania was officially represented by Archbishop Gergely Kovács of the Archdiocese of Alba Iulia, and Bishop József Csaba Pál of Timișoara (Romania) also participated in the synod as an invited member of the Hungarian minority.

These facts help explain the notable activity of Serbian and Transylvanian Hungarian ecclesiastical institutions on Facebook. However, they do not fully account for the relatively low communication activity of dioceses and parishes within Hungary itself. The presence of two Greek Catholic participants – a theology professor and an archbishop – also sheds light on the high proportion of posts related to the Hungarian Greek Catholic community within the overall corpus of Hungarian-language content. The denominational and institutional affiliations of the synod participants are also reflected in the territorial distribution of the content, which showed a marked overrepresentation of locations connected to Hungarian communities beyond the borders of Hungary, as well as to the Greek Catholic tradition.

The role of ecclesiastical media outlets within the analysed discourse deserves particular attention. These stakeholders are prominently represented in the synod-related social media communication, both in terms of their number and the volume of content they produce. At the same time, it is evident that Facebook functions as a secondary platform for them. Their primary activity is carried out through their main channels – as online news portals, print journals or magazines, radio stations, or television channels. Their use of social media primarily serves to increase visibility, promote their content, and reach new audience segments. Given their position, they are able to publish or repost reports, interviews, and summaries related to synodal events. However, as media outlets, they are generally not in a position to facilitate the local implementation of the synodal process through event organization or other community initiatives.

This role would primarily fall within the capacity of institutional actors situated at higher levels of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and in territorial centres – those already in contact with the faithful and local communities. While such stakeholders (e.g. dioceses, church institutions) participated in the Facebook discourse at a rate comparable to that of media outlets, it is observable that these institutional centres are, to a large extent, content with merely providing information. They predominantly share news reports originally published either on their own websites or on ecclesiastical media platforms. Clear messages, explicit positions, or calls to action are only rarely communicated.

Accounts and posts featuring strong, personal messages are more characteristic of church actors who personally participated in synodal events, as well as smaller ecclesial movements. Behind this type of active social media communication lies a strong sense of personal commitment and experience, or, in the case of movements, a pre-existing culture of community engagement and participation. Finally, it is worth emphasizing that the temporal structure of the Hungarian-language social media discourse on the synodal process closely follows the central synodal events, suggesting that the majority of posts consist of news reports providing updates on the synodal assemblies themselves.

Our study is exploratory in nature, aiming to uncover only the most basic patterns in the quantitative assessment of the synod’s representation on Hungarian-language Facebook. We have fulfilled our objective of identifying and characterizing the key participants in the Hungarian-language social media discourse on the synodal process. The novelty of this study lies primarily in the multi-perspective analysis of a large dataset, which has also raised numerous questions and topics worthy of further investigation.

Limitations and future research

The continuation of the research can take several directions. For instance, while beyond the scope of this paper, it would be important to examine the discourse surrounding the synodal process on Instagram, as well as to conduct an in-depth functional analysis of Hungarian websites4 created to support the synodal journey online. Similarly, we have not yet carried out a content analysis of the 491 Facebook posts collected in the current research – an endeavour that could offer a deeper understanding of the patterns identified above. Targeted sampling could also be used to explore the synod-related content published on the websites of Hungarian dioceses and monastic orders, in order to gain a more accurate picture of how domestic church structures have contributed to shaping the synod’s public presence in Hungary. In addition, the communal dimension of the discourse – that is, user comments and interactions – also merits analysis, in order to understand what forms of participation social media offers to the faithful in engaging with the synodal process. It would also be useful to compare the media representation of synodality in Hungary with the coverage of other, less extraordinary and less divisive events or processes in the life of the Church, in order to determine the extent to which the observed underrepresentation is related to the controversial reception of the synodal path within the Hungarian Catholic Church itself.

The limitations of our research include uncertainties related to the archiving and accessibility of Facebook content published at earlier dates, as well as the opaque nature of Facebook’s search algorithm. These factors limit the comprehensiveness of data collection. Regarding data processing, a further limitation is that our analysis primarily focused on metadata and external characteristics of the posts, while the textual content itself was not subject to in-depth analysis.

Recommendations

Our research revealed that, in relation to a topic as significant as the synodal transformation of the Catholic Church, the higher-level organisational units of the Hungarian Catholic Church displayed only moderate communicative activity on the social media platform Facebook. In contrast, religious media outlets, faith-based movements and organisations, as well as Hungarian-speaking ecclesial stakeholders outside Hungary, were considerably more active in engaging social media in the mediatization of the synodal process. We recommend that domestic church leaders critically review their own synod-related communication activities and consider and adopt social media as a strategic tool for communication with the faithful, with particular attention to its affordances for fostering participation, enhancing engagement, and incorporating the voices and contributions of believers.

At the same time, it is important to emphasize that while communication is a crucial and foundational component of synodal transformation, communication about the synod cannot substitute for the actual realization of synodal goals.

References

- Andok Mónika (2021) Trends in Online Religious Processes during the Coronavirus Pandemic in Hungary—Digital Media Use and Generational Differences. Religions, 12(10). 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100808

- Andok Mónika (2023a) Comparative Analysis of Digital Media Usage in Hungarian Religious Communities. Millah: Journal of Religious Studies, 22(1). 181–204. https://doi.org/10.20885/millah.vol22.iss1.art7

- Andok Mónika (2023b) Digitális vallás. Az új információs technológiák hatása a vallásokra, vallási közösségekre Magyarországon. Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó – Ludovika Egyetemi Kiadó. https://doi.org/10.1556/9789634549574

- Andok Mónika – Páprádiné Szilczl Dóra – Radetzky András (2023) Hungarian Religious Creatives-Comparative Analysis. Religions, Jan. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010097.

- Berger, Peter. L. – Luckmann, Thomas (1966) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, NY, Anchor Books.

- Bárdi Nándor – Fedinec Csilla – Szarka László eds. (2008) Kisebbségi magyar közösségek a 20. században. Budapest, Gondolat Kiadó – MTA Kisebbségkutató Intézet.

- Brazal, Agnes M. (2023) Synodality and the New Media. Theological Studies 84(1). 95–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00405639221150888

- Bruns, Axel (2008) Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. New York, Peter Lang.

- Burgess, Jean – Green, Joshua (2009) YouTube. Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge – Malden, Polity Press.

- Cameli, Louis (2024) Rediscovering the Historical Roots of Synodality and Co-Responsibility. Church Life Journal, July 11.

https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/rediscovering-the-historical-roots-of-synodality-and-co-responsibility/ - Fuchs, Christian (2014) Social Media: A Critical Introduction. London, Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446270066

- Glózer Rita (2022) Részvétel, média, kultúra. Videóblogok a részvételi kultúrában. Budapest, Gondolat Kiadó.

- Ihejirika, Walter C. (2024) How can our media be actors of synodality? Strategies on how journalists and their media institutions can embark on Pope Francis’ call to a “synodal conversion”, by what means, for what purposes. LaCroix International, January 30. https://international.la-croix.com/news/ethics/how-can-our-media-be-actors-of-synodality/19086

- Jenkins, Henry (2006) Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. New York – London, New York University Press.

- Mattei, Giampaolo (2024) Synodality: A conversion aimed at becoming more missionary. Vatican News, 26 October. https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2024-10/synodality-a-conversion-aimed-at-becoming-more-missionary.html

- Miller, Katherine (2012) Organizational Communication: Approaches and Processes. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- Orosz György – Szabó Gergő – Berkecz Péter – Szántó Zsolt – Farkas Richárd (2023) Advancing Hungarian Text Processing with HuSpaCy: Efficient and Accurate NLP Pipelines. In Ekštein, Kamil – Frantisek Pártl – Miloslav Konopik (2023 eds.) Text, Speech, and Dialogue, Berlin – Heidelberg, Springer. 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40498-6_6

- Papp Z. Attila – Kovács Eszter – Kováts András (2020) Magyar diaszpóra és az anyaország. Diaszporizáció és diaszpórapolitika. In Kovách, Imre (2020 ed.) Mobilitás és integráció a magyar társadalomban. Budapest, Argumentum – Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont. 295–324.

- Radetzky András (2023) Religious and Ecclesiastical Media in the Hungarian Electronic Media Ecosystem. Khazanah Journal of Religion and Technology, 1 (2). 33–39. https://doi.org/10.15575/kjrt.v1i2.374

- Sebők Miklós – Ring Orsolya – Máté Ákos (2021) Szövegbányászat és Mesterséges Intelligencia R-ben. Budapest, Typotex.

- Schütz, Alfred (1932) Der sinnhafte Aufbau der sozialen Welt: eine Einleitung in die verstehende Soziologie. Wien, J. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-3108-4

- Tikk Domonkos ed. (2007): Szövegbányászat. Budapest, Typotex.

- Zaccaria, Francesco (2024) Synodality and Decision-Making Processes: Towards New Bodies of Participation in the Church. Religions 2024/15, 54. 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010054 - van Dijck, José – Poell, Thomas – de Waal, Martijn (2018) The Platform Society. Oxford, University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190889760.001.0001

Appendix

Table 1

A brief description of the stakeholders identified in the research (n = 491).

| Type of stake-holder | Facebook account holder | Brief introduction of the account holder | Number of likes and followers of the Facebook account |

| church, diocese, archdiocese | |||

| Gyulafehérvári Katolikus Érsekség | The Archdiocese of Gyulafehervár is the Roman Catholic diocese in Romania, covering the territory of historical Transylvania. | 8,6K / 12K | |

| Hajdúdorogi Főegyházmegye | The Archdiocese of Hajdúdorog, together with the Diocese of Miskolc and the Diocese of Nyíregyháza, form the Greek Catholic Metropolitical Church of Hungary (abbreviated as the Greek Catholic Metropolia). | 4,4K / 5,4K | |

| Olaszországi Magyar Katolikus Misszió | The St. Stephen’s Foundation in Rome has a threefold mission: to help and care for Hungarian pilgrims coming to Rome, to provide pastoral care for the local Hungarian Catholic community, and to nurture the linguistic and cultural roots of Hungarians living in Rome. | 1,1K / 1,6K | |

| Magyar Katolikus Egyház | A collective name for the organisations of the universal Catholic Church in Hungary. In other words, it is the totality of the sub-churches of the universal Catholic Church in Hungary. | 12K / 16K | |

| Nagyváradi Egyházmegye | The Roman Catholic Diocese of Oradea is a diocese of the Catholic Church in Romania. It belongs to the Archdiocese of Bucharest. | 9,1K / 15K | |

| Szabadkai Egyházmegye | The Diocese of Subotica is the ecclesiastical unit of the Roman Catholic Church in Vojvodina, in the territory of the Republic of Serbia, which includes the southern part of Bačka. | 6,7K / 7,4K | |

| Váci Egyházmegye | One of the dioceses of the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary, it covers the area around Hatvan and Szolnok, as well as Nógrád county and Pest county east of the Danube. The diocese’s episcopal seat is in the city of Vác. | 6K / 8K | |

| Veszprémi Érsekség | The Archdiocese of Veszprém is one of the twelve Roman Catholic dioceses in Hungary, one of the dioceses founded by St Stephen. It was the first bishopric to be established in Hungary. | 8,2K / 12K | |

| Nyíregyházi Egyházmegye | The Diocese of Nyíregyháza is a Greek Catholic diocese in Hungary. It was founded by Pope Francis on 19 March 2015 as part of the Metropolitan Church of Hungary. The diocese has its seat in Nyí-regyháza, in the same administrative area as the county of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg. | 8,7K / 10K | |

| local community, parish | |||

| Bátaszéki Római Katolikus Plébánia | Roman Catholic parish in Hungary, in Tolna county, Bátaszék. | 1,3K / 1,5K | |

| Kapisztrán Szent János Kápolna | Traditional Catholic Chapel in Újbuda (Budapest). The parishioners of the chapel are primarily served by the Pro Hungaria Sacra – Priestly Brotherhood priests for Holy Hungary. The main goal of the PHS community is the resacralisation of the Hungarian nation and the revitalisation of Hungarian religious customs and tradition, primarily through spiritual renewal and the graces of the sacraments (according to their introduction). | 951 / 1K | |

| Kartali Szent Erzsébet Egyházközség | Roman Catholic parish in Kartal, Hungary, Pest county. | 725 / 904 | |

| Magyar Katolikusok Berlinben és Brandenburgban | Facebook page for Hungarian Catholics living in Berlin and Brandenburg. | 560 | |

| Mária Neve Római Katolikus Plébánia Solt | Roman Catholic parish in Hungary, Bács-Kiskun county, Solton. | 337 | |

| Pilisszántói Plébánia | Roman Catholic parish in Hungary, Pest county, Pilisszánto. | 229 | |

| Szent Rita Templom | Roman Catholic parish and pilgrimage spot in Budapest, Hungary. | 3,4K / 3,6 | |

| ecclesial community, movement | |||

| Katolikus Hitoktatók | The website and community of the 31st Bolyai Summer Academy – Roman Catholic Teachers of the Faith section (Romania). | 66 / 90 | |

| Óföldeáki Zarándoklat | Facebook account linked to a website that summarises and informs about the preparations for the International Eucharistic Congress (ICE) in the Diocese of Szeged-Csanád. The website publishes the dates and reports of programmes, meetings, trainings, and prayer events. | 556 / 602 | |

| Új Város | Facebook account linked to the Új Város magazine. The Új Város is the successor to the public magazine of the Focolare Movement, founded in 1989, and is owned by the Új Város Foundation, which runs the website and the Facebook account. The Focolare Movement is a spiritual renewal movement within the Catholic Church, founded in Italy in 1943. | 1,7 / 1,9 | |

| church-run institution | |||

| Seminarium Incarnatæ Sapientiæ (Gyulafehérvár) | The Roman Catholic Seminary of the Incarnate Wisdom in Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia, Romania). Operated by the Archdiocese of Gyulafehervár. | 4,8 / 5,9 | |

| other church-related organisation | |||

| Beregszászi Pásztor Ferenc Közösségi és Zarándokház | A community centre and pilgrimage centre run by the Roman Catholic parish of Beregszász (Berehovo, Ukraine). | 795 / 804 | |

| Egyházi Fejlesztők | Church Developers is a team of Christian professionals committed to supporting church communities, organisations, and leaders who are ready to grow. | 977 / 1K | |

| Militia Templi – Christi pauperum Militum Ordo | The „Order of the Knights Templar—Order of the Poor Knights of Christ” is a Roman Catholic lay order of knights. Reestablished in 1979, the Order of the Knights Templar and its Hungarian preceptory were authorised to operate in Hungary in 1999 by the Archbishop of Eger, then President of the Hungarian Catholic Bishops’ Conference. | n.d. | |

| clergy person, theologian, monk, monastic order | |||

| Jezsuiták | The official Facebook page of the Society of Jesus of Hungary (Hungarian Jesuits). | 17 K / 19 K | |

| Csiszár Klára | Klára Antónia Csiszár (Szatmárnémeti, 1981 -) is a Hungarian Catholic theologian and university professor. Vice Rector and Dean of the Faculty of Theology of the Catholic University of Linz. One of the expert participants of the Synod on Synodality. | 2,4 K | |

| Sajgó Szabolcs | Szabolcs Sajgó SJ (Budapest, 7 August 1951-) Jesuit monk, writer, poet, poetry translator, director of the Párbeszéd Háza (House of Dialogue) in Budapest. | 17K | |

| Kocsis Fülöp | Greek Catholic monk, bishop, since 20 March 2015, Archbishop-Metropolitan of the Archdiocese of Hajdúdorog. Since 2008, he has been the head of the diocese, which was elevated to archdiocese by Pope Francis. | 4,2K / 6,4K | |

| religious magazine, news site, TV, radio, news agency | |||

| Bizony Isten | Facebook account related to the religious programmes of Duna Television. | 62 K | |

| Bihari Napló | Hungarian-language newspaper of the same name, published in Oradea, Romania. | 23K / 25K | |

| Zarándok.ma | Catholic.ma / Zarándok.ma magazine is run by the „St Bartholomew’s Bells” Media Mission Foundation (Pécs, Hungary) | 71K / 84K | |

| Magyar Kurir | The Hungarian Catholic Bishops’ Conference’s news portal has been online since 2005. It was founded in 1911. | 42K / 53K | |

| Romkat.ro és Vasárnap hetilap | A Transylvanian-edited Hungarian-language Catholic portal in Romania, it provides information on the life of the four dioceses that founded its publishing house. An ecumenical openness characterises it. | ||

| Vatican News | The new information system of the Holy See, run by the Secretariat for Communi-cation, the new dicastery of the Roman Curia, created by Pope Francis in 2015. | 4,9 / 4,9 | |

| Vigilia Szerkesztőség | Hungarian Catholic literary and scientific journal. | 5,9 K | |

| Mária Rádió | Radio Maria is a communication tool of a Catholic-oriented organisation. In Hungary, it is not run by the Hungarian Catholic Church but by a foundation owned by a secular individual who runs the radio for secular apostolic purposes. The radio is run by a priest and is operated mainly by volunteers, free of charge, as a goodwill activity. | 64K / 120K | |

| Szemlélek | The magazine, maintained by the Szemlélek Alapítvány, is supported by donations and advertising. It aims to promote a critical approach and social dialogue. | 31K | |

| Martinus Könyv- és Folyóirat Kiadó | Publisher of the book and magazine of the Diocese of Szombathely (Hungary). | 1K / 1K | |

| individual | |||

| Józsa Emmi | An individual with a public Facebook account. | 167 | |

| thematic account, collection page | |||

| Ferenc pápa beszédei, írásai | The account, kept by the Piarist monk Endre Tőzsér, contains Pope Francis’s complete speeches and writings, translated inaccurately into Hungarian. | 12K | |

| educational and higher education institutions | |||

| BBTE Római Katolikus Teológiai Kar | Faculty of Roman Catholic Theology, Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca (Cluj-Napoca, Romania). | 1,8K / 2,1K | |

| BBTE Vallás, Kultúra, Társadalom Doktori Iskola | Doctoral programme „Religion, Culture, Society”, Faculty of Roman Catholic Theology, Babes-Bolyai University, Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca, Romania). | 215 / 241 | |

| Pázmány jogi kar – PPKE ÁJK | Pázmány Péter Catholic University Faculty of Law and Political Sciences | 6,7K / 7,5 K | |

| Xantus János Általános Iskola | One of the oldest primary schools in Csíkszereda (Miercurea-Ciuc, Romania) | 336 / 416 | |

| Pápai Magyar Egyházi Intézet | A college for the further training ordained Hungarian priests in Rome since 1940. | 916 / 1,1K | |

- https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2021/october/documents/20211009-apertura-camminosinodale.html [accessed 4 February 2025]↩

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1029770/facebook-users-hungary/ (as of July 2024).↩

- Collecting social media data has become extremely difficult since Meta shut down Crowdtangle, an essential online research tool often used by communication and media researchers, on 14 August 2024. The Content Library provided as a replacement offered limited possibilities for retrieving social media data in several ways, so we had to consider another solution. Therefore, we developed a complex search and data mining method, which only allowed us to conduct exploratory, non-representative research.↩

- https://megujul.hu/, https://egyhaz2030.hu/, https://dunapartiiskola.sapientia.hu/↩