Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools and Applications Among Ecclesiastical Journalists

Hivatkozás:

Rajki Zoltán & Andok Mónika & Radetzky András & Szilczl Dóra (2025). Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools and Applications Among Ecclesiastical Journalists. Jel-Kép: Kommunikáció, Közvélemény, Média, (2.) 77-95. 10.20520/JEL-KEP.2025.2.77

Abstract

Our presentation focuses on the topic and relationship between religion, ecclesiastical journalism and media technology, artificial intelligence. In the first part of our presentation, we will review how artificial intelligence is changing the media industry on a global scale. As a result, what new inequalities are created in the media industry. After that, we will present which processes related to new AI applications can be automated in the field of media content production. And we also cover the transformation of the role of a journalist and the perception of a journalist’s role. In our presentation, we will demonstrate what artificial intelligence applications Hungarian religious and ecclesiastical media content creators use in their work, what attitudes they have regarding artificial intelligence, and what journalistic ethical issues concern them. We also present whether religious institutional or editorial regulations regarding the applicability of artificial intelligence are implemented or not. In our presentation, we show the results of qualitative research conducted in the fall of 2023 and quantitative research conducted in the spring of 2024. In the fall of 2023, we conducted in-depth interviews with 40 journalists regarding artificial intelligence. The gender and generational differences are clearly visible from the results. Building on this, we prepared a questionnaire in the spring of 2024, in which we also asked about the attitudes of religious and nonreligious content producers regarding artificial intelligence. In our lecture, we present the results of this research. What differences can be shown between religious and non-religious content creators in the use of artificial intelligence tools during their journalistic work.

Keywords

The relationship between technical and scientific tools and journalism

In the evolution and development of journalism and mass communication, the dominant communication technologies of the given era always played a decisive role, which later – in an institutionalized form – brought about a new era in the history of the press. Starting from the 19th century professionalization of the printing industry and its efficiency-enhancing innovations to the transformation of news gathering, from the telegraph to satellite networks (Briggs – Burke 2004, Barbier – Lavenier 2004). In the last third of the 19th century, the changes in the publishing of newspapers and the electronic textualization of press texts in the United States show many analogies with the processes associated with artificial intelligence today. Only at that time was a distinction made between „electronic insider / outsider” in terms of existing or lacking journalistic skills in the field of creating texts (Marvin 1988: 15-17). The university -level journalism courses established at that time included the need for scholarship in their curricula (Schudson 2001). Walter Lippmann wanted to further strengthen this at the beginning of the 20th century, who raised the possibility of Scientific Journalism in 1920. Based on this, only scientific (verified) methods could be used in journalism. At the same time, Lippmann attempts to turn journalism itself into a science. The continuation of this direction is Precision Journalism, launched in the 1970s and announced by Phillip Meyer. He only differs from Lippmann’s program in that Meyer would not lend natural science, but only social science methods to journalism. He developed a complete methodology for his theory (Meyer 1989, Wien 2005). In fact, we can see a technologically enhanced version of the same scientific program in Database Journalism, which started in the 1960s and was based on early computer technology. According to his followers, the cornerstones of journalistic work since the second half of the 20th century have been various databases. The press must rely on scientifically verifiable data and facts that can be obtained from them. The 1990 version of these ideas was already called CAR – Computer Assisted Reporting, and the IBM 7090 machine was used for it, so in this case we can already see a strong advance of network communication in journalistic work (Gehrke – Mielniczuk 2017). Just as the effective use of computer data played an increasingly important role in journalists’ tools, data journalism (data journalism, data-driven journalism) appeared from the beginning of the 2000s, primarily in the United States and to a lesser extent in Hungary. For the high-quality cultivation of data journalism, on the one hand, finding and filtering data, and on the other hand, new types of storytelling and visualization belong to the basic journalistic skills (Gray – Chambers – Bounegru 2012, Szabó 2022). This created an environment for journalism, which is also called smart journalism (Marconi 2020). This includes journalism using drones or 360 footages as well as the use of artificial intelligence.

Changes in journalism under the influence of artificial intelligence

The release of ChatGPT in the fall of 2022 directed considerable public attention towards artificial intelligence, however, scientific literature has long been concerned with its operationalization possibilities and risks in various segments and institutions of society. Such questions have arisen in the production sectors, in connection with the fourth industrial revolution, as well as in the fields of health care, education and journalism (Jiang et al. 2017, Ribeiro et al. 2021, Yang et al. 2021, Rajki 2023). Changes affecting journalism can also be observed globally, especially in the operation of the media sector, in the methods of content production and distribution, and in the perception of the role of journalists. The literature generally predicts positive effects on the global media landscape, as artificial intelligence can facilitate and make the media system more efficient. According to a March 2023 report by Goldman Sachs, “… the widespread adoption of artificial intelligence could increase labour productivity and increase global GDP by 7% per year over a 10-year period.” (Briggs – Kodnani 2023). However, the rate of growth will be different, and the lag of the Global South is expected to increase in news production, distribution, and the media industry in general. North America held 39.0% of the AI in media and entertainment market in 2021, and this share is expected to grow (AI in Media & Entertainment Market Industry Outlook 2022-2032). At the same time, it is necessary to provide AI-related education on a global level so that users can effectively use the opportunities provided by the application of AI and understand the operation of the media environment supported by AI.

According to Sahota (2023), the expected changes at the industry level are characterized by a significant expansion: the value of the artificial intelligence market in the media and entertainment industry is estimated to reach 124.48 billion dollars by 2028, with a compound annual growth rate of 31.89% (CAGR). New business models are emerging in the media industry, such as more efficient paywall applications such as Piano or Sophi. In contrast, the New York Times sued OpenAI in 2023 for alleged copyright infringement, accusing them of using millions of their articles to train ChatGPT without their permission (Grynbaum – Mac, 2023). In contrast, Axel Springer has an agreement with OpenAI that could bring the company tens of millions of euros in annual revenue by giving OpenAI access to content from Bild, Politico and Business Insider (Axel Springer and OpenAI, 2023). OpenAI also entered into a similar agreement with the AP news agency, which allows access to AP’s historical archives and new content (Newman 2024:15).

Changes are expected not only in the field of copyrights, but also in the broader regulatory environment of the media industry, a process that has already begun with the adoption of the European Union’s Digital Services Act. All of this suggests that it becomes necessary to rethink the issues of normativity and control in the field of journalism and the media. As a result of industry changes, it is possible to offer more personalized offers to consumers of media content, without language restrictions.

The next big wave of changes expected in the field of media content production is primarily related to the introduction of artificial intelligence applications. These applications can help journalists in many ways, including trend monitoring, forecasting, news gathering and data verification. Tools such as Pinpoint AI, Tabula AI and Open Refine can be highlighted in this area. The applications most noticeable to readers are involved in content generation, including translation, audio-to-text, and text and image generation. Narrativa AI, Radar AI, Amazon Polly, Trint, ChatGPT, DALL-E and Sora can be mentioned in this category. Artificial intelligence can also be useful in the editing phase of journalistic work, such as content summarization, extracting or rewriting. The Agolo AI and ETX Studio applications can be highlighted here. Archiving is supported by Archive AI, moderation by Membrace AI and Toloka AI, while optimization of sharing and recommendation is supported by Crux AI.

Journalists and media workers can also feel the changes related to artificial intelligence. Journalists’ attitudes towards AI are changing; according to current research, most of them see AI as a tool that increases their creativity and efficiency. Only a minority of them believe that their work could be completely replaced by artificial intelligence. Ethical issues play a particularly significant role in relation to the journalistic application of AI. An important question for representatives of the profession is how to ensure the authenticity, accountability and verifiability of the content generated by AI. Ensuring transparency and issues of responsibility arising during application also require special attention.

To develop appropriate responses to these challenges in the journalism profession, it is necessary to share good practices and knowledge, as well as further training provided by professional organizations. Examples include the „Welcome to AI – USC Annenberg Report 2024” pages published by the University of South Carolina’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, and the „JournalismAI” training courses organized by the Society of Professional Journalists and LSE.

International pilot research on the relationship between artificial intelligence and journalism

The European Union of Journalists (EJ) is an international civil professional interest protection organization founded in 1962 in San Remo, Italy. According to its articles of association, the purpose of the organization is, among other things, to unite the media world that believes in the need for European integration on a democratic basis, and is committed to the promotion and protection of press freedom and access to information sources, to expand knowledge about the European Union and other European organizations, and to inform the public about the powers of the relevant institutions and about his activity. The organization places special emphasis on regional information, cross-border cooperation, and regions with ethnic and linguistic minorities. Finally, it considers it its task to promote the development of the journalistic profession and the conditions that make it possible within Europe. The association holds a general assembly combined with a professional conference at least once a year.

Between October 26-29, 2023, the EJ held its annual general meeting in Nice, France. This gave us the opportunity to involve many international journalists in the research. We conducted a total of ten semi-structured interviews with journalists of eight nationalities (Italian, Bulgarian, German, Romanian, French, Spanish, Georgian and American). The subjects represented several fields of journalism, including culture, public life, politics and science. They were all experienced journalists, with at least ten, but most of them more than twenty years of experience. Regarding their age, two people were between 30-49 years old, six people were between 55-60 years old, and 2 people were over 65 years old. The interviews were conducted in English. In this component of our research, we decided on semi-structured interviews because we were not interested in personality or identity, but primarily in the opinions and knowledge we hoped to learn from the subject. The questions of the research did not refer to the subject, the individual experience of social phenomena, but to a precisely defined, concrete sub-problem, i.e. the circumstances and motivations of the journalistic application of artificial intelligence. Éva Kovács draws attention to the fact that, in this sense, the theoretical background and methodological objectives of structured in-depth interviews are not essentially different from those of social science research using statistical data or archival sources. Even though the interview is made up of subjective answers, it is not aimed at revealing the social embeddedness of the subject, but rather at learning about certain competencies and attitudes. „During the structured in-depth interview, we want to know something from people, not about people.” (Feischmidt – Kovács 2007).

When preparing the plan for the semi-structured interview, we took care to ask some standard questions, such as age, field of expertise, and number of years spent in the profession.

We used several open-ended questions. The wording of these questions is not fixed in advance because it is adapted to the respondent’s style and standards. We briefly described the topic of our research, as we participated in a professional conference held specifically on this topic. We deepened the research topic with several interwoven questions (chain of questions). This loosely fixed interview structure leaves room for exploring the subject’s deeper motivations. The guiding thread of our interviews included pre-formulated primary (open) and secondary (also open) questions. Thus, the basic structure of the interview guaranteed certain basic information from the outset, and on the other hand, it remained flexible so that those contents that were not planned but belonged to the framework topic could also be discussed. Our goal was to ensure that both we and our subjects had a certain scope for action and development. We processed the information obtained from the interviews with a qualitative approach, i.e. primarily the exploration of individual characteristics (behavioural patterns, attitudes, opinions) was considered primary, while the numerical evaluation of the data was not considered.

From the answers, three areas were clearly outlined in connection with the application of artificial intelligence: (1.) the issue of regulation/self-regulation, (2.) pragmatic, practical issues of use, and (3.) the topic of fears, dangers and future opportunities.

Regarding the regulation, the subjects were of the same opinion, namely that global regulation is needed because regional regulation of artificial intelligence cannot provide a solution to most dilemmas and problems, which already raise elementary questions. One of our subjects directly expressed his opinion that “in its current state, technology is already stretching the legal framework known so far.” According to the regulations in force (both in the USA and in the EU), large, global online platforms are not responsible for the content placed, stored, or transported on them, as a rule, as the producer of the content is responsible. In principle, this is supervised and controlled by the authority of the state where the given service provider is established. However, this general regulatory principle needs to be clarified, especially with regard to the rapid spread and development of artificial intelligence technology.

Currently, the legislators are also running a race against time. The DSA, the Digital Services Act, came into force in the European Union, requiring large platforms (e.g. Google, Meta st.) to take measures to prevent the spread of illegal goods, services or content online. For example, mechanisms to allow users to flag such content and for platforms to work with „trusted whistleblowers”.

The DSA regulates intermediary providers more comprehensively than ever before, especially online platforms such as online marketplaces, social and content sharing sites, app stores, as well as online travel and accommodation platforms and operators of AI applications. The most important goal of the regulation is to act against illegal and harmful content, to prevent the deliberate spread of fake news, and to protect the safety and fundamental rights of users. Overall, it creates a safer online environment in which they can more easily report illegal content, goods and services available on the sites.

DSA was preceded, if only by a few months, in the USA by 47 U.S.C. § 230 of the Biden-Harris Executive Order, which, although not yet at the legislative level, regulated the use of AI for the first time. The presidential decree seeks to name several issues and threats related to artificial intelligence (AI). According to the regulation, new guidelines will have to be developed to guarantee the safety of AI devices. The most important findings of the decree:

- Developers of high-performance AI systems must share the results of their security tests with the federal government before releasing their products to users.

- The security of the system will be tested by a so-called „red team”, searching for potential weak points.

- Special attention is paid to artificial intelligence models involved in scientific and biological projects.

- For the first time in the world, it was made mandatory that content generated by AI must be watermarked, such as audio, image, video, and text files.

- Increased control is ordered at companies regarding compliance with data protection regulations.

- It states that discrimination must be reduced in AI models.

In our study, the subjects we interviewed primarily highlighted copyright (personal and property rights, as well as the set of so-called neighbouring rights) and criminal law (personality rights, defamation, hate speech) as problems to be solved. Regarding the first, the biggest dilemma is that copyright only protects human-made works:

„Anything we create – be it a study, a poem, a website, a graphic, a piece of music, a film or other literary, scientific or artistic work, an architectural plan or a computer program, or even a database – is subject to copyright protection if has an individual-original character. The adaptation of another author’s work is also protected by copyright if it also has an individual and original character, provided of course that the author of the original work has consented to the adaptation. (…) Copyright belongs to the person who created the work, i.e. the author.”

AI „works” from human creations protected by copyright, but the „works” it creates are not the result of human creation, so they cannot be protected by copyright. In the meantime, it is not possible to know exactly from which works, databases, and information the AI created the text, image, motion picture, or anything else. At the same time, in terms of copyright law, the very process by which AI-generated content is created can already be protected by copyright.

In the sense of criminal law, the most important question is who is responsible if a content created by AI, be it textual, image, auditory or audiovisual, violates the constitutional rights, honour, and grace of others, or defames them. The legal premise is that a crime can only be committed by a private person (natural person in the language of the law), non-natural persons (companies, associations, companies, foundations) cannot do this. In the current legal system, this fundamentally excludes the criminalization of an algorithm or software. In criminal cases of defamation or defamation, intent must be proven, which is not the case with AI. However, it is definitely in favour of technology, that with its help we can do things much more efficiently than before, e.g. to recognize hate speech, since it has unique linguistic, syntactic, and stylistic characteristics, and an amount of content that is opaque and unmanageable to humans can carry this type of law violation.

Turning back to the main issue of regulation, according to the professional point of view, both legal and self-regulation will be necessary for all elements of the value chain. The elements of the value chain were identified by journalists as follows:

- the state as the main regulator,

- tech companies, as manufacturers and producers of technology (hardware + software);

- mass communication content producers (journalists, gatekeepers, institutional communicators, independent context producers);

- advertisers, i.e. businesses engaged in business communication;

- finally, the consumers themselves.

While the state is involved in regulation, the other actors primarily see the solution in self-regulation. At the same time, the moral and ethical rules of conduct for the use of artificial intelligence are not yet linked to a principle of profitability that would make the stakeholders economically interested in the ethical use of AI. As Péter Zsolt pointed out earlier, the real transformation in the development of media ethics occurred when ethics appeared in the market as a principle of profitability. In other words, it was worthwhile for newspapers, radio stations, and television channels to behave ethically, not to lie, to be objective, balanced, in short, to be fair. In the absence of this quality, tabloid entertainment would probably dominate even more than it does today. Presumably, it would include lies. Of course, the main question remains: does the inner conviction of the media lead the journalist to behave ethically, or does he act this way under the pressure of the audience? (Zsolt 2005:129) Crystallization of this principle in connection with the use of AI still requires time. Time also plays a key role in self-regulation in other respects. Making every moral decision takes time. However, time is a luxury in the media, mainly because of the news competition. The templates that help journalists to make the right moral decision were created to resolve this situation. The question is, how much time does the profession need to create such a template that can also be used in practice for the application of artificial intelligence. AI can open a new era in this regard as well, because it can make journalism more productive, which can have measurable economic consequences. A positive consequence is that the increase in productivity can attract capital to the industry, but a negative one is that it is expected to lead to a decrease in the number of professional journalists (like when robots or other new technologies replace the person who used to do assembly in, for example, a car factory). Most of our subjects see AI as a tool that increases their ability to work, their efficiency, and ultimately their productivity. Marshall McLuhan, who has been an indispensable author in media studies since the 1960s, one of the main findings of his work is exactly that the media transform human nature and culture, create new forms of perception and practice. He looked for the basic characteristics of each medium and investigated how they affect people and culture by „extending” the senses and abilities in different ways. (McLuhan 2001)

According to Péter Fodor and Péter L. Varga, the extension, expansion, and replacement of human senses or activities in McLuhan’s media science can also be described with the concept of prosthesis, which goes back to Sigmund Freud’s idea of culture. In his 1930 study entitled Unhealthy Feelings in Culture, Freud puts it as follows: „With all his means, man perfects both his movement and sensory organs, or removes the limitations of their functioning. […] He corrects the disability of his eye lenses with glasses, investigates the far distance with binoculars, overcomes the limit of perception marked by the structure of his retina with a microscope. […] Man has become, so to speak, a kind of prosthetic god, it is great if he relies on all his aids, but they have not grown with him and on occasion cause him a lot of trouble.” (cited by Fodor – L. Varga 2018:447)

During the data collection, we encountered considerations very close to this line of thought. The greatest attraction of the application of AI is currently the so-called “generative possibilities” that help the user, in our case the journalist, to create specific content. However, communication specialists working in the field of public relations also highlight, e.g. the possibilities inherent in story generation. (We note that this profession does not mean inventing stories, but the telling of events that have happened in a narrative.) AI intelligence can help in

storytelling to create thinking schemes that endow real events and happenings with meaning. The guiding thread of these, the arrangement of the story thread, the way of compilation can be imagined because of the „work” of AI.

In the same way, they look expectantly at work processes where it is necessary to process a large amount and volume of information. For instance, it could be processing the material of a complex court case that has been going on for years or summarizing the results of scientific research that is difficult for a journalist to comprehend. This is especially important in view of the fact that one of the tasks of the journalistic profession, if not the most important one, is to simplify, understand and accept the often-complicated social reality for media consumers. But in general, the speed and efficiency of material collection will also be accelerated by AI, which can lead to a further increase in the speed of media rotation. There are also great expectations for the translation of foreign language texts. AI-based translation programs have existed for many years, but in recent years their efficiency and accuracy have increased significantly. Analytical possibilities should also be highlighted. In general, AI can bring unprecedented efficiency in data analysis, rankings, database sorting, data filtering, cleaning, and so on. According to expectations, the creative industry can also benefit a lot from its operation: brainstorming, branding, image generation, creating illustrations (e.g. converting text into graphs), to mention only a few of the answers. Among voice-based AI applications, the conversion of written texts into speech and voice transformation (a given person speaks a given language) stand out.

A recurring element was the world of news, news editing and the role of AI in it. We have already touched on ethical considerations, but the method of use was a recurring element. Here, mainly the search for events, the generation of social media content related to news, SEO (search engine optimization) support, and AI-based fact checking came up most often. Kevin Rose, a staff member of the New York Times, put it this way: „AI generated journalism is a »pink slime« journalism.”, that is, AI generated journalism is something like a food additive. Finally, based on the data we collected in connection with the use, it can be clearly established that the key to success is the right specification, i.e, the more precisely we define the task, the more detailed instructions we give, the more accurate the result will be.

This brings us to the third area, the review of threats and opportunities. “The risk is here”. This means the danger is present. It’s how one of our subjects put it. The new technology can contribute to the deterioration of language abilities, the degradation of human linguistic and combinatorial competences. It can be a hotbed for conspiracy theories, spreading political (or any other type of) propaganda. As we alluded to earlier, the amount of plagiarized content may increase, especially given that the AI user himself may not be aware of what resources and how the technology was used when performing the task he specified. All of this may result in a general loss of trust in the media, which may have unpredictable long-term consequences from an economic point of view, but also from the point of view of the proper functioning of democratic societies, democratic publicity, and social dialogue.

Artificial intelligence poses a danger if people become complacent, if we apply it superficially, if we use it after insufficiently thorough research, if we do not want to understand the processes, if we do not check the facts thoroughly enough, or if we lose our own creativity. As Richard Balwin, director of the Geneva-based Geneva Graduate Institute, put it: „It’s not AI that’s going to take your job, it’s someone using AI.” To be precise: someone who uses AI better.

Regarding the potential dangers, Rhodri Talfan Davies, the BBC’s Director of Nations, published the institution’s AI-related principles in October 2023. According to the document, artificial intelligence can present new and significant risks if not properly exploited. These include the ethical issues we have discussed before, legal and copyright challenges, and

significant risks around misinformation and bias. These risks are real and should not be underestimated, requiring both foresight and vigilance. However, they believe that a responsible approach to the use of technology can help mitigate some of these risks.

In the meantime, they argue, artificial intelligence could provide a serious opportunity for the BBC to deepen and amplify its mission, enabling it to deliver even more value to audiences and society in general. AI can also help them work more efficiently and effectively in many areas, including manufacturing workflows and back-office work. Unprecedented opportunities are being created to deepen the institution’s most important mission, i.e. its activities for the benefit of the public. The BBC places a high value on talent and creativity. You are priority. However, no technology can replicate or replace human creativity. Authentic, human storytelling by the best reporters, writers and hosts in their fields should always be preferred. According to the document, the next period should explore how they can use generative artificial intelligence in order to open new horizons in this work. The resolution points to one of the key motives for the ethical use of technology: transparent application. Trust is the basis of the relationship between the media and the public. Media workers must always remain accountable to the public for all content and services they produce and publish. You need to be transparent and clear with your audience when generative AI appears in your content and media delivery. Human supervision will be an important step in publishing generative AI content.

The largest international organization of institutional communicators (PR professionals), ICCO, has also published the principles according to which PR professionals can use artificial intelligence (Warsaw Principles). According to the organization, the rapid development of artificial intelligence is both a challenge and an opportunity for the public relations profession, but AI cannot replace the work of PR professionals. The purpose of the ten principles is to help the PR profession in how to approach artificial intelligence. According to the profession’s self-definition, the responsibility of PR professionals, armed with this new technology, is to prioritize scientifically based facts in the communication of organizations, ensuring that all messages are transparent and reliable. The position of the profession is also important because public relations itself is essentially a strategy of trust, the profession of building and maintaining trust (in organizations), so institutional communicators are the most skilled in the matter of trust. The resolution names the following criteria as the most important:

- transparency, disclosure and credibility;

- accuracy, fact-checking and the fight against disinformation;

- data protection and responsible sharing;

- detecting, mitigating and accepting biases;

- intellectual property, copyright compliance and media literacy;

- human supervision, intervention and cooperation;

- contextual understanding, adaptation and personalization;

- responsible automation and efficiency;

- continuous monitoring, evaluation and feedback;

- ethical professional development, education and artificial intelligence advocacy.

Although there is a strong convergence of responses across all three themes, some national specificities can be identified. The issue of regulation was the one most emphasised by our two German respondents, but our Bulgarian and Georgian respondents also explained and justified their ideas in more detail than the others, with the criminal law aspects dominating in all three cases. In terms of the practical application of technology, two journalists from the South (ES, IT) emphasised storytelling, while data analysis, background work, data processing and

visualisation seemed to be of paramount importance to their US counterpart. Unsurprisingly, news considerations were prominent for the US colleague. This is not a surprising result, given that in liberal media models the journalist is primarily in the role of recording and conveying events, whereas in Europe, the journalistic self-definition of the so-called democratic-corporatist models is somewhat different: here the journalist is not only called upon to present reality, but also, in a sense, to shape it through opinion pieces. Among the dangers, the French and Romanian colleagues stressed the danger of the transformation of language – as they put it – of its degradation, while the others were united in their disinformation, propaganda and misinformation. It should be stressed that this component of our study is a deep dive and does not allow us to draw generalizable conclusions on the national specificities of AI use. Our intention was primarily to identify international trends and attitudes towards the technology.

Building on the experiences of the international survey, we continued the second part of our research, now among Hungarian journalists in the spring of 2024.

Empirical research: Church journalists and media technology and artificial intelligence topic and relationship

Research goals, sampling, method

Our study focuses on the topic and relationship between church journalism and media technology and artificial intelligence, compared to those working in the non-church field. During our research, we seek answers to the following questions:

1. What artificial intelligence applications do content producers working in the Hungarian church media use as private individuals or in the course of their work?

2. What is their attitude towards artificial intelligence?

During the sampling, church and non-church media institutions, editorial offices, and organizations were contacted to send our e-mail regarding the completion of our online questionnaire to their journalists and media professionals. The online questionnaire was made available on the Survio.com website between February 22 and April 8, 2024. Our self-made questionnaire was based on our qualitative (in-depth interview) research conducted in the fall of 2023. The questionnaire used contained 28 questions, 4 open-ended and 24 closed-ended.

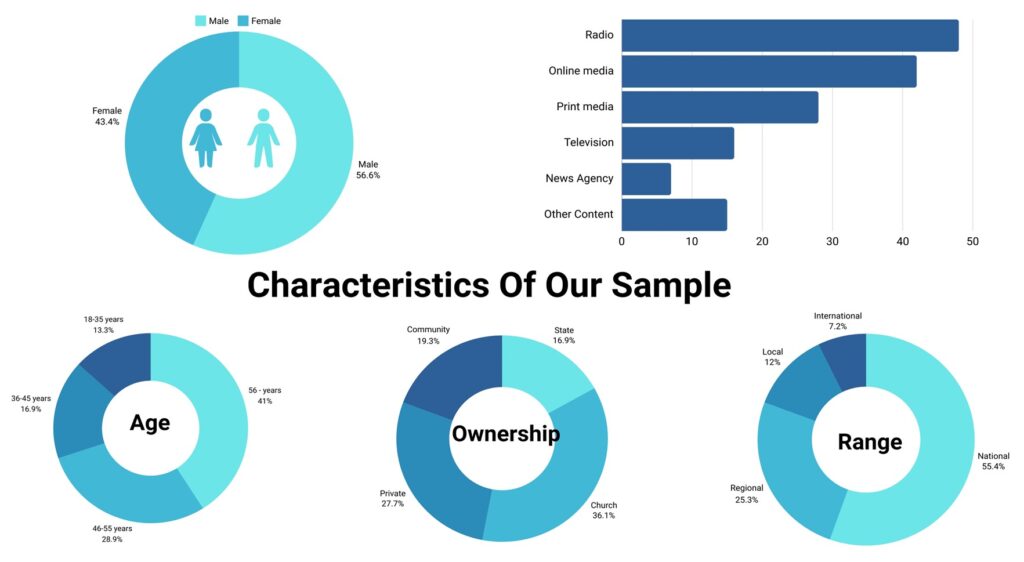

The questionnaire was filled out by 83 people, all of whom were journalists and media professionals. 56.6% of those who completed the questionnaire were men and 43.4% were women. Regarding their age distribution, our questionnaire was mostly filled out by those aged 56 and over (41%) and those between 46 and 55 (28.9%). The proportion of 36-45-year-olds was 16.9%, while the proportion of under-35s barely exceeded 10% (18-25-year-olds: 3.6%, 26-35-year-olds: 9.6%).

Regarding their place of work, the highest proportion came from radio broadcasting (48.2%), the online press (42.2%), and the printed press (27.7%). Television (15.7%), news agencies (7.2%), and the proportion of workers in other online content production did not reach 20%. More than a third (36.1%) of our respondents worked for church-owned media companies, a quarter (27.7%) privately owned, a fifth (19.3%) community-owned, and 16.9% state-owned media companies. More than 50% of them worked for national (55.4%) and a quarter of them regional (25.3%) media companies. The proportion of local (12%) and international (7.2%) mediums in our sample was not significant.

Table 1

Characteristics of Sample (gender, age, media, ownership, range)

We also examined the period spent as a media worker. Based on the age data, it is not surprising that 60% of our applicants have worked in the field for more than 2 decades. The proportion of workers in other categories was between 3-13%.

Regarding the subject of our research, it is worth examining the above basic data in the division of church-owned and non-church-owned mediums. Due to the low number of items (n=83), we have combined them so that the different chi-square tests show more reliable results.

It is clear from the research data that the demographic conditions are more balanced among the employees of non-church-owned companies. Thus, the ratio of the sexes is essentially the same, while in the case of church mediums, the male/female ratio is two-thirds to one-third. Regarding the age distribution, in the case of both types of ownership, we see an over-representation of age groups over 46, but this value already reaches 80% in the case of church journalists, while in the case of non-church media it is 34%. In the case of individual media types, the proportion of people working in the online press among non-church-owned media reaches almost 50%, while only a third of our church-owned employees work in this field. In the case of those working in the field of radio broadcasting, we see a difference of almost 20%. Among our respondents, the proportion of church media workers in the field of radio broadcasting is 63%, while in the case of non-church mediums, this figure is 40%. Among the above, the various chi-square tests only showed a significant difference in the field of radio.

Our sample cannot be considered representative, and due to the size of our sample, we can only make cautious statements. The data was processed using the IBM SPSS 28.0 software, and MS Excel was used to create the figures.

The results of the research

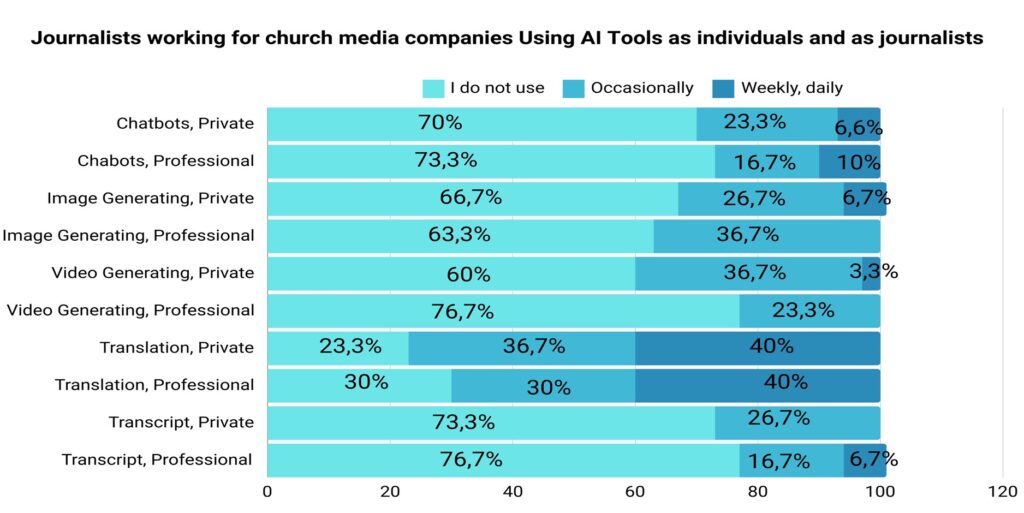

In the first part of our research, we examined how often church journalists use AI tools in the five areas we listed (chatbots, image and video generation, translation, transcript) as private individuals and as professional media content producers. It is clear from the answers received

that in four areas (chatbots, image and video generation tools, transcript, sound generation applications) at least two-thirds of the respondents do not use applications based on AI technology either as individuals or as journalists. The least used were transcript and text generation tools. Most of the existing users of AI devices in the four areas mentioned above classified themselves as occasional users. A maximum of 10% of church journalists used these applications at least weekly.

The only exception was translation applications. 40% of journalists working for church media who filled out the questionnaire regularly (at least weekly) used Deepl or one of its alternatives. This value is true both in the personal and journalistic fields. The proportion of occasional users is not far behind this (36.7% and 30%). The proportion of those who do not use AI-based translation tools at all was 30% or less.

Table 2

Journalist working for church media company using AI tools

Based on the data in Table 2, we can find a greater difference in the use of image generating tools in the changing field of church and non-church media workers. Furthermore, the proportion of those working at non-church media who use them as a work tool at least once a week is significantly higher than that of their fellow church journalists (20.7% vs. 0%), and the proportion of those who use these tools occasionally (17% vs. 36.7 %). The proportion of those who do not use image editing tools at all is almost the same in both groups, so there is a significant difference in the intensity of use among those who use the tools. The Pearson chi-square (.036) and the Likelihood test (.007) indicate a significant difference, but the low due to the number of elements, further tests will be required.

When we summarize the data, we find that out of the five areas we have listed, church members use an AI device on average in 2.07 areas as private individuals, while non-church members use AI tools in 1.94 areas. As a work tool, this average has decreased to 1.8 for church members and to 1.77 areas for non-church media workers. Therefore, we do not see any significant differences between the two investigated groups. As individuals, 16.9% of the interviewed journalists (church: 10%, non-church: 20.8%), while 19.3% of journalists (church:13.3%, non-church:23.6%) did not use an AI tool in the area we mentioned, 8.4% of private individuals and 4.8% media workers use some kind of AI application in each of the areas we listed.

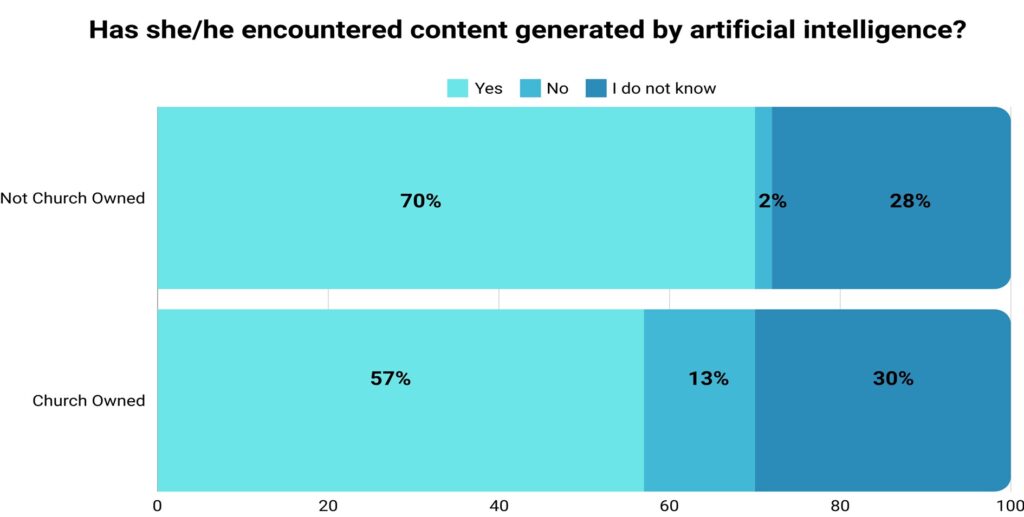

In our next question, we were interested in whether the interviewees said they had encountered content created by artificial intelligence. We assume that we may come across content generated by AI daily during our lives. Table 3. illustrates the obtained data in the breakdown of church and non-church journalists.

Table 3

Has she/he encountered content generated by AI

From the data in Table 3, it is clear that the majority (56.7% vs. 69.8%) of those working in the field of ecclesiastical and non-ecclesiastical journalism have already come across content generated by AI. In both categories, the proportion of those who answered „I don’t know” is almost the same (30% vs. 28.3%). If we start from the previously mentioned assumption that everyone has probably already come across AI-generated content in some form, then based on the data in Table 1, we can also assume that people working at church media are less likely to recognize products made with artificial intelligence than their peers working at church institutions 1.9% vs. 13.3%). However, chi-square tests did not show a significant relationship.

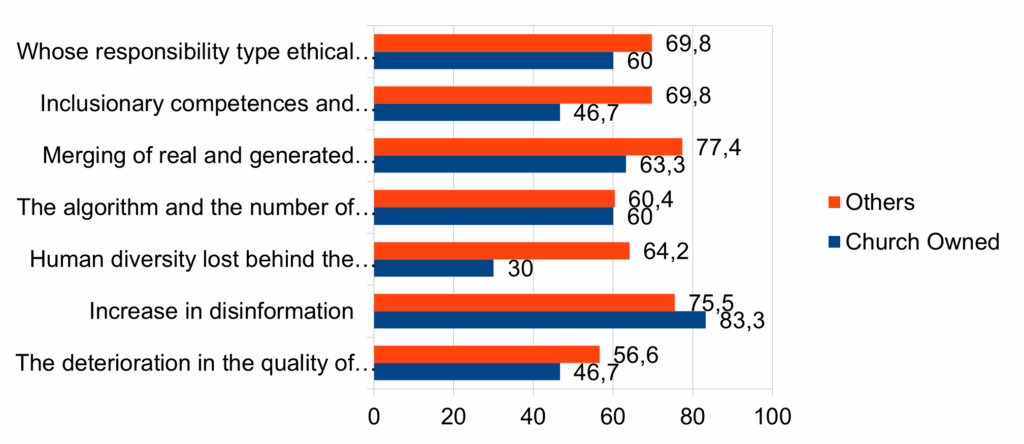

In the next part of our questionnaire, we were interested in how much the journalists consider the introduction of AI tools as a challenge in the seven areas we have listed. With the help of Table 2, we have depicted the proportion of church and non-church journalists who consider the expansion of AI tools in the following areas to be a significant challenge.

From the data in Table 4, it is clear that most of the church journalists consider the growth of disinformation to be the biggest challenge (83.3%), which is caused by the blurring of real and generated reality (63.3%), the spread of click-bait texts (60%), and „whose responsibility type of ethical questions” (60%) follow. Almost every second church journalist considered the lack of inclusive competences and critical senses (46.7%) and the deterioration of the quality of journalism (46.7%) to be a significant challenge. Among church journalists, the fewest (30%) were afraid that „human diversity will be lost behind the neutral tone of AI” (30%).

Table 4

The proportion of church and non-church media workers who consider the following areas to be a significant challenge, data in percentage

If we compare the opinions of church and non-church media workers, it can be noticed that in five of the seven areas we have listed (1. lack of reception competences and critical sense, 2. blurring of real and generated reality, 3. WE are lost behind the neutral tone human diversity, 4. Deterioration of the quality of journalism, 5. Whose responsibility type of ethical questions) journalists working for non-church media forecast a significant challenge. Only in the field of the growth of disinformation did we experience greater concern among the interns working for church media. However, the statistical analyses showed a significant difference in only two areas, namely the lack of inclusive competences and critical sense (46.7% vs. 69.8%) and the neutral tone of AI (30% vs. 62%) human diversity is lost behind it. In both cases, non-church media workers were more pessimistic.

It is also worth looking at how many of the seven areas we identified were considered significant challenges on average, and how many of the media professionals we identified were identified as significant challenges. Based on the above-mentioned data, it was no surprise that we obtained a higher value among non-church members (4.74 vs. 3.97). So, they perceive the risks in the spread of AI devices better, but we got a high value for both groups. However, the T-test showed no significant difference.

In the next question, we asked you how much you agree with some common opinions about the impact of AI on the world of media. In table 5, we collected the percentage of church and non-church journalists who agree with the six statements we formulated.

The data in Table 5. also confirm our previous findings that those working at church media are somewhat more optimistic about the use of AI tools in journalism than their peers working at non-church media. Thus, in their circle, a higher proportion of them agree with the statement that AI helps their work (73.3% vs. 45.3%), and that its use is useful in journalism (53.3% vs. 37.7%), and in their circle it is lower the proportion of those who consider the use of AI in journalism to be dangerous (60% vs. 71.7%). Like those working at non-church media, a third of them were afraid of AI applications in their workplace, and the vast majority of journalists from both groups agree that the use of AI tools in journalism is neither ethically nor legally regulated. However, the chi-square tests indicated a serious significant difference in only one area. According to this, among those who work for church media, the proportion of those who think that AI applications help them in their work is significantly higher.

Table 5

Percentage of Respondents Who Agree With The Following Statements Among Ecclesiastical and Non-ecclesiastical Journalists

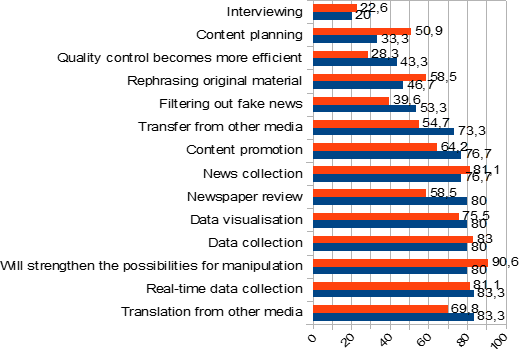

In the next section, we also examined how, according to the interviewees, tools based on artificial intelligence are transforming the various areas of journalism. In figure 4, we have summarized the proportion of those working in the church and non-church media fields who predict a major transformation in the areas we have specified due to the spread of the use of AI tools.

Table 6

Which Areas Of Journalism Are Being Transformed To A Large Extent by AI, According To Those Working In Church And Non-ecclesiastical Media, in Percentages

From the data in Table 6, it is clear that at least three-quarters of church newspaper writers in eight of the 14 areas listed by us believe that AI will greatly transform journalism in the future. Almost half of these are related to data and information collection in some form, such as real-time data collection (83.3%), the data collection process (80%), news collection (76.7%), and the field of data visualization (80%). But the vast majority of those who filled out the questionnaire forecast a major transformation in the areas of translation from other media (83.3%), newspaper reviews (80%), and promotion of content (80%). One of the eight areas can be clearly considered a negative process, which is nothing more than the strengthening of manipulation possibilities. According to 83.3% of the church journalists who filled out the questionnaire, this phenomenon will mostly occur.

According to more than half of the journalists working for church media, the expansion of AI will greatly transform the „taking over from other media” (73.3%) and the process of filtering out fake news (53.3%). According to nearly 50% of church journalists, AI will make quality control more effective (43.3%). The latter two data are compared with the fact that 80% of them believe that AI will greatly strengthen the possibilities of manipulation in the field of journalism. This indicates that most church journalists also see the dangers inherent in the strengthening of the new technology.

Interestingly, according to 46.7% of church journalists who filled out the questionnaire, the spread of AI tools will greatly transform the process of „paraphrasing original materials”. Knowing only the performance of the most well-known free-to-use chatbots (e.g. ChatGPT, BingAI, Google Gemini) after appropriate prompting, I personally see greater „potential” in AI devices in this area. The tools are even able to rewrite the text we specify in the style we request. Of course, the process requires additional human correction, but by using AI we can save considerable time and energy. According to two-thirds, four-fifths of church journalists, AI tools will not change the process of content planning (66.6%) or interviewing (80%) much either. In the former case, in my opinion, the AI tools, in addition to the appropriate expertise, can also provide users with a strong topic-specific help in brainstorming and content planning.

Based on Table 6., we see a difference of almost 20% between church and non-church journalists in three areas. In contrast to 80% of church journalists, 58.5% of non-church journalists believe that the process of newspaper review will be greatly transformed by tools based on artificial intelligence (21.5% difference). The difference between the two examined groups does not differ much in terms of taking over material from other media. In this case, too, the majority of church journalists predicted that AI tools would have a great transformative effect in this area (73.3% vs. 54.7%). The great transformative effect of AI tools on content planning was predicted more among non-church journalists (33.3% vs. 50.9%).

In six areas, we could see a 10-15% difference between the two investigated groups. Thus, the impact of quality control on efficiency (43.3% vs. 28.3%), filtering out fake news (53.3% vs. 39.6%), promoting content (76.7% vs. 64.2%), and regarding the impact of AI tools in the field of translation from other media (83.3% vs. 69.8%), we can see a higher ratio among church journalists. On the other hand, among non-church journalists, a higher proportion believed that the spread of AI tools will greatly strengthen the various possibilities of manipulation (80% vs. 90.6%), and they predicted a great transformative effect of AI tools in the process of paraphrasing original materials (46.7% vs. 58.5%). In the other areas, we found no significant differences between the two investigated groups.

However, chi-square tests indicated a smaller significant relationship between church and non-church journalists in only one area. And this means that „the process of paper review is greatly transformed” by tools based on artificial intelligence.

Based on the data in Table 6., it seems that in our sample, among church journalists, the proportion of those who believe that artificial intelligence-based tools will greatly transform the various processes of journalism is somewhat higher. This idea is confirmed by the fact that out of the 14 areas we have listed, church journalists believed that artificial intelligence-based tools will greatly transform the journalism process in an average of 9.17 areas, while among non-church journalists this value is only 8.58 volt. However, the T-test did not indicate a significant difference.

Summary

In summary, we can say that the use of AI devices has not gained ground among church and non-journalists in Hungary, either for personal or professional use. Only the use of translation applications stands out among them. Despite this, three-quarters of those working at church media admitted that AI tools help their work, and just over 50% considered their use useful in the field of journalism. Nevertheless, most of them are more afraid of the risks of using AI devices. Most feared the growth of disinformation (over 80%), but many also treated the blurring of the effect between the real and the generated world (60%), as well as the „mechanization” of the media (see algorithm-centeredness, click hunting, 60%), as key risk factors. It is therefore understandable that 60% of church journalists considered the application of AI in the field of journalism to be dangerous. The existence of ethical and legal problems associated with the use of AI was considered particularly problematic. 60% of church journalists considered the existence of „whose responsibility” type of ethical questions to be a significant challenge, and only a sixth of them believed that the use of AI tools in journalism is ethically and legally properly regulated.

When analysing the data, it seems that the employees of non-church media companies are in most cases more critical of the spread of the use of AI than their colleagues working at church media.

Among the limitations of the research, the sample with a small number of items and the sampling with a non-random method should be highlighted, and the chosen sampling tool – an online questionnaire – may have affected the composition of the respondents to a certain extent. However, the results of the research point to the areas, problems, concerns, and challenges that professionals working in the media in Hungary face as a result of the expansion of AI. We believe it is particularly important to further investigate this issue in the field of church media, as the spread of AI tools can represent not only opportunities, but also risks.

Limitations of the Research and Future Directions

The limitations of our research include a non-representative sample (n = 83), non-random sampling, and biases resulting from the use of an online questionnaire. The predominance of older age groups (69.9% over 46 years) and church media workers (36.1%), coupled with the selection effect of respondents’ motivation (e.g., interest in AI) and constraints on technological access (e.g., digital skills, internet access), render the results non-generalizable to the Hungarian journalist population. The small sample size further limits the reliability of statistical analyses, particularly for subgroup comparisons.

The results are exploratory and suitable for examining the AI usage habits and attitudes of church and non-church journalists within a limited group. The alignment of qualitative and quantitative data strengthens the research’s internal validity, though results must be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

Future research should investigate AI use with larger, random samples, mixed methodologies (e.g., paper-based questionnaires, interviews), and a longitudinal approach. Targeted sampling is needed to include underrepresented groups (e.g., younger journalists), alongside studies of specific AI tools and international comparisons. A dedicated analysis of the motivational and technological limitations of online surveys could further refine the methodology.

References

- Barbier, Frederic – Lavenir, Catherine Berto (2004) A média története: Diderot-tól az internetig. Budapest, Osiris.

- Baumol, William J. (1966) Performing arts. In: Baumol, William J. & Bowen, Willam G. (1966 eds.) The world of economics. London, Palgrave Macmillan UK. 544–548.

- Burke, Peter – Briggs, Asa (2004) A média társadalomtörténete. Gutenbergtől az internetig. Budapest, Napvilág Kiadó.

- Feischmidt Margit – Kovács Éva szerk. (2007) Kvalitatív módszerek az empirikus társadalom- és kultúrakutatásban. Budapest, ELTE BTK Művészetelméleti és Médiakutatási Intézet.

- Gehrke, Marília – Mielniczuk, Luciana (2017) Philip Meyer, the outsider who created Precision Journalism. Intexto. 4–13.

- Gray, Jonathan; Chambers, Lily & Bounegru, Liliana (2012) The data journalism handbook: How journalists can use data to improve the news. ” O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- Jiang, Fei – Jiang, Yong – Zhi, Hui – Dong, Yi – Li, Hao – Ma, Sufeng – Wang, Yongjun (2017) Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future. Stroke and vascular neurology, 2(4).

- Marconi, Francesco (2020) Newsmakers: Artificial intelligence and the future of journalism. New York, Columbia University Press.

- Marvin, Caroline (1988) When old technologies were new: Thinking about electric communication in the late nineteenth century. Oxford, Oxford University Press, USA.

- McLuhan, Marshall (2001) A Gutenberg-galaxis: a tipográfiai ember létrejötte. Budapest, Trezor.

- Meyer, Phillip (1989) The New Precision Journalism. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Newman, Nic (2024) Journalism, media and technology trends and predictions 2024. Oxford, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Rajki Zoltán (2023) A mesterséges intelligencián alapuló alkalmazások a bölcsészet-, társadalomtudomány és az oktatás területén. Humán Innovációs Szemle, 14(2). 4–21.

- Ribeiro, Jorge – Lima, Rui – Eckhardt, Tiago – Paiva, Sara (2021) Robotic process automation and artificial intelligence in industry 4.0–a literature review. Procedia Computer Science, 181. 51–58.

- Schudson, Michael (2001) The objectivity norm in American journalism. Journalism, 2(2). 149–170.

- Szabó Krisztián (2022) Adatalapú vizuális médiatartalmak Magyarországon. Média-kutató, 23(2). 15–34.

- Yang, Stephen J. – Ogata, Hiroaki – Matsui, Tatsunori – Chen, Nian-Shing (2021) Human-centered artificial intelligence in education: Seeing the invisible through the visible. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100008.

- Varga Péter – Fodor Péter (2018). Marshall McLuhan. In Kricsfalusi, Beatrix – Kulcsár Szabó Ernő – Molnár Gábor Tamás – Tamás Ábel (2018 eds.). Média-és kultúratudomány: Kézikönyv. Budapest, Ráció Kiadó.

- Wien, Charlotte (2005) Defining objectivity within journalism. NORDICOM review, 26(2). 3–15.

- Zsolt Péter (2005) Médiaháromszög. Vác, EU-Synergon.

Sources:

- AI in Media & Entertainment Market Industry Outlook (2022–2032). Available: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/ai-in-media-and-entertainment-market (Download: 202503.01.)

- Axel Springer and OpenAI partner to deepen beneficial use of AI in journalism. 13.12.2023. Available: https://www.axelspringer.com/en/ax-press-release/axel-springer-and-openai-partner-to-deepen-beneficial-use-of-ai-in-journalism (Download: 22/08/2025.)

- Briggs, Joseph – Kodnani, Devesh (2023) Generative AI could raise global GDP by 7%. Goldman Sachs 05 APR 2023 Available:

https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/pages/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent.html (Download: 22/08/2025) - Grynbaum, Michael M. – Mac, Ryan (2023) The Times Sues OpenAI and Microsoft Over A.I. Use of Copyrighted Work. The New York Times 2023. 12. 27. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/27/business/media/new-york-times-open-ai-microsoft-lawsuit.html (Download: 22/08/2025.)

- LSE is JournalismAI. Available:

https://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/polis/JournalismAI

(Download: 22/08/2025.) - Sahota, Neil (2023) The Transformative Impact of AI on Media and Entertainment Sectors. Available: https://www.neilsahota.com/the-transformative-impact-of-ai-on-media-and-entertainment-sectors/ (Download: 22/08/2025.)

- Society of Professional Journalists – Available: https://www.journaliststoolbox.org/2023/05/25/ai-tools-for-journalists/

(Download: 22/08/2025.) - The Digital Service Act (DSA) Available: https://www.eu-digital-services-act.com/ (Download: 22/08/2025.)

- The USC Annenberg Relevance Report. Available: https://annenberg.usc.edu/research/center-public-relations/relevance-report (Download: 22/08/2025.)

AI tools:

- Agolo AI – https://www.agolo.com/

- Amazon Polly – https://aws.amazon.com/polly/

- Archive AI – https://aiarchive.io/

- Chat GPT – https://chat.openai.com/

- Crux AI – https://www.getcrux.ai/

- Dall-E – https://www.dall-efree.com/

- ETX studio – https://en.etxstudio.com/

- Membrace AI – https://membrace.ai/

- Narrativa AI – https://www.narrativa.com/

- Open Refine – https://openrefine.org/

- Piano – Analytics and Activation https://piano.io/

- Pinpoint AI – https://www.pinpointai.com/index.html

- Radar AI – https://app.radarai.com/

- Sophi – https://www.sophi.io/paywalls/

- Sora – https://openai.com/sora

- Tabula AI – https://www.tabula.io/

- Toloka AI – https://toloka.ai/

- Trint – https://www.printsai.com/